More than 15 years ago I first set sight on the floating Petermann Gletscher when the United States’ Coast Guard Cutter Healy visited north-west Greenland for the first time on 10th August of 2003. We only had to sail 20 km into the fjord to reach a flat expanse of glacier ice that stuck less than 5 m (15 feet) above the sea. In 2012 and 2015 we had to sail another 20 km, because two large calving events had shortened the glacier farther back than it has since first records were kept in 1876. The terminus was also much higher, almost 25 m (75 feet) above the sea:

Terminus of Petermann Gletscher 5th August 2015 from aboard the Swedish icebreaker Oden. View is to the south-east. [Photo Credit: Andreas Muenchow]

I published more detailed results on observed glacier change and estimated melt rates with Drs. Laurie Padman and Helen Fricker in the Journal of Glaciology from which I take these two figures:

Petermann Gletscher’s two large calving events in 2010 and 2012 as seen from MODIS satellite. The glacier is floating on the ocean seaward of the grounding line indicated by the thick black line. Black areas are open ocean water, white is ice. Adapted from Muenchow et al., 2014.

Time series from 1876 to 2014 of the length of Petermann Gletscher as measured from its grounding line at y=0 km. Triangles are observations while lines indicate a steady 1 km per year advance. The insert shows three maps of observed glacier shapes. From Muenchow et al., 2014.

Back in 2003 the glacier advanced about 1 km each year and it does so still. Almost the same, but not exactly, because the removal of 6 “Manhattans” in 2010 and 2012 increased the forward speed some, that is, the glacier now moves faster forward than it did before. Many sensors placed on the glacier measured this speeding, but the glacier also gets thinner as it speeds up. It is stretched thin. I published this back in 2016 together with Drs. Laurie Padman, Keith Nicholls, and my PhD student Peter Washam in Oceanography:

Speed at which Petermann Gletscher moves out into the sea from many different measurements. The glacier moves more slowly over land (negative distances) than it does floating over the ocean (positive distances). Estimates made after 2012 are about 10-20 % higher than RADARSAT estimates before that date. From Muenchow et al., 2016.

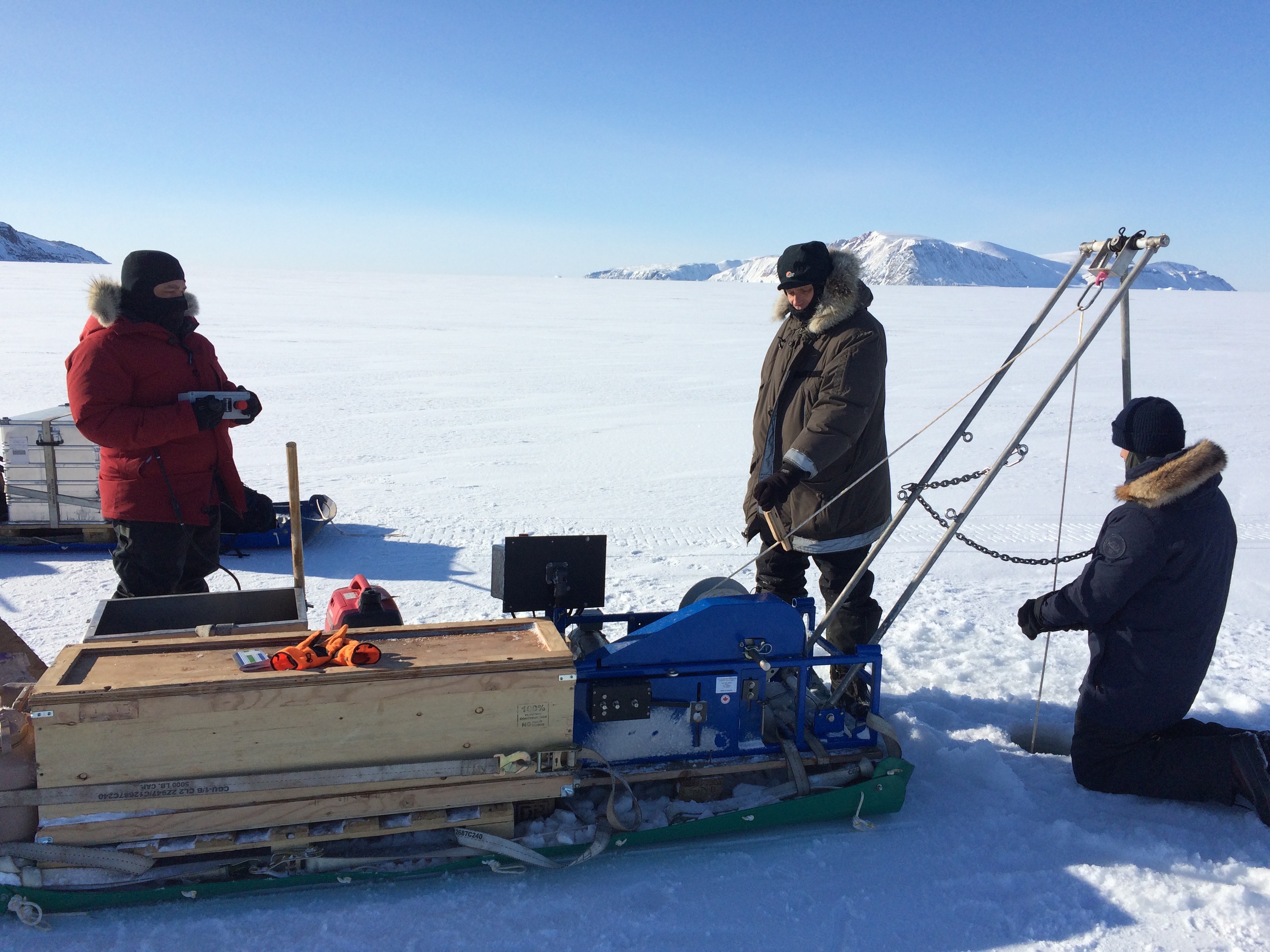

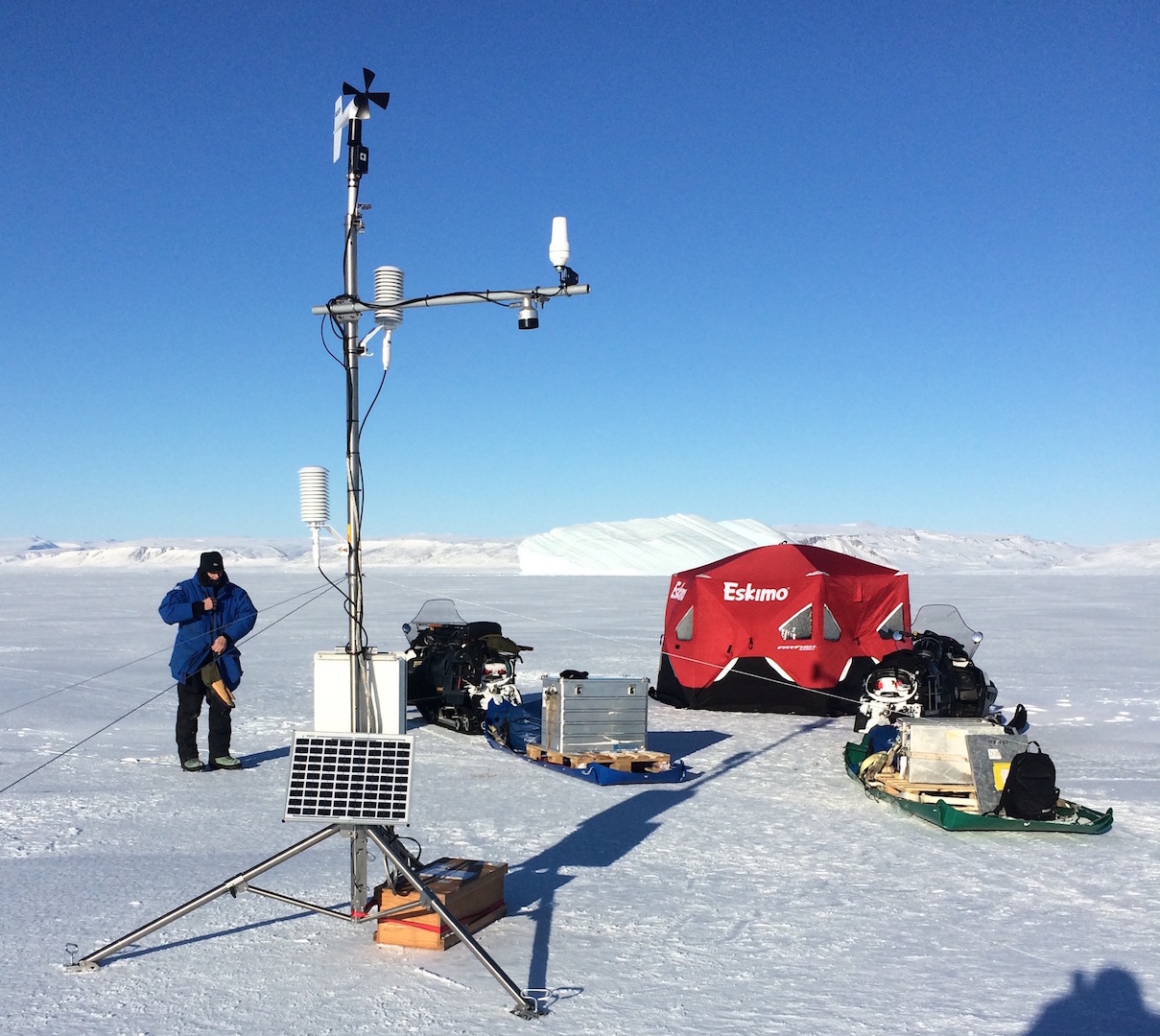

With substantial help from the British Antarctic Survey we installed in 2015 a small ocean observing system under the floating glacier. It transmitted data from 800 meters (2400 feet) below the 100 m (300 feet) thick glacier ice via cables connected to a weather station. We sucessfully repaired the station (as well as a Danish weather station nearby) that stopped transmitting data via satellites in 2016. Two journalists of the Washington Post, Chris Mooney and Whitney Shefte joined Keith Nicholls and myself. Their outstanding and accurate reporting of our work includes video and graphics for a wider audience that you can find at this link:

Washington Post Video of 2016 Petermann Gletscher Site Visit

The ocean and glacier data were worked over carefully by Peter Washam who defended his dissertation last month. Dr. Washam moved to Georgia Tech in Atlanta to work with Dr. Britney Schmidt whose interests relate to the ice-covered oceans below some moons of Jupiter. Peter connected ocean temperature and salinity with ice radar and remote sensing data to estimate how much the glacier is melted by the ocean and how the ocean does this. His main result will be published later this year in the Journal of Glaciology [Added July-12, 2019: Published online as Washam et al., 2019 at the Journal of Glaciology.], that is

“… This increase in basal melt rates confirms the direct link between summer atmospheric warming around Greenland and enhanced ocean-forced melting of its remaining ice shelves. We attribute this enhanced melting to increased discharge of subglacial runoff into the ocean at the grounding line, which strengthens under-ice currents and drives a greater ocean heat flux toward the ice base…”

The next large calving will be no surprise: Large fractures cross much of the glacier. They are visible about 10-20 km behind the current terminus and are discussed and closely monitored almost every day at the excellent site of Greenland Enthusiasts from all walks of life who post at

https://forum.arctic-sea-ice.net/index.php/topic,53.600.html

Furthermore, a new sophisticated computer model of Petermann Gletscher reveals that the loss of this large “still attached” ice island is already gone from the glacier in terms of the friction that it provides along the sidewalls. Another way of putting this, all it takes is a little wiggle or bump and the separation will become visible. Dr. Martin Rueckamp just published this study in the Journal of Geophysical Research.

There is much more to be explored with regard to Petermann. Here are some of the readings and writings that I have done with many fellow sailors through uncertain climates:

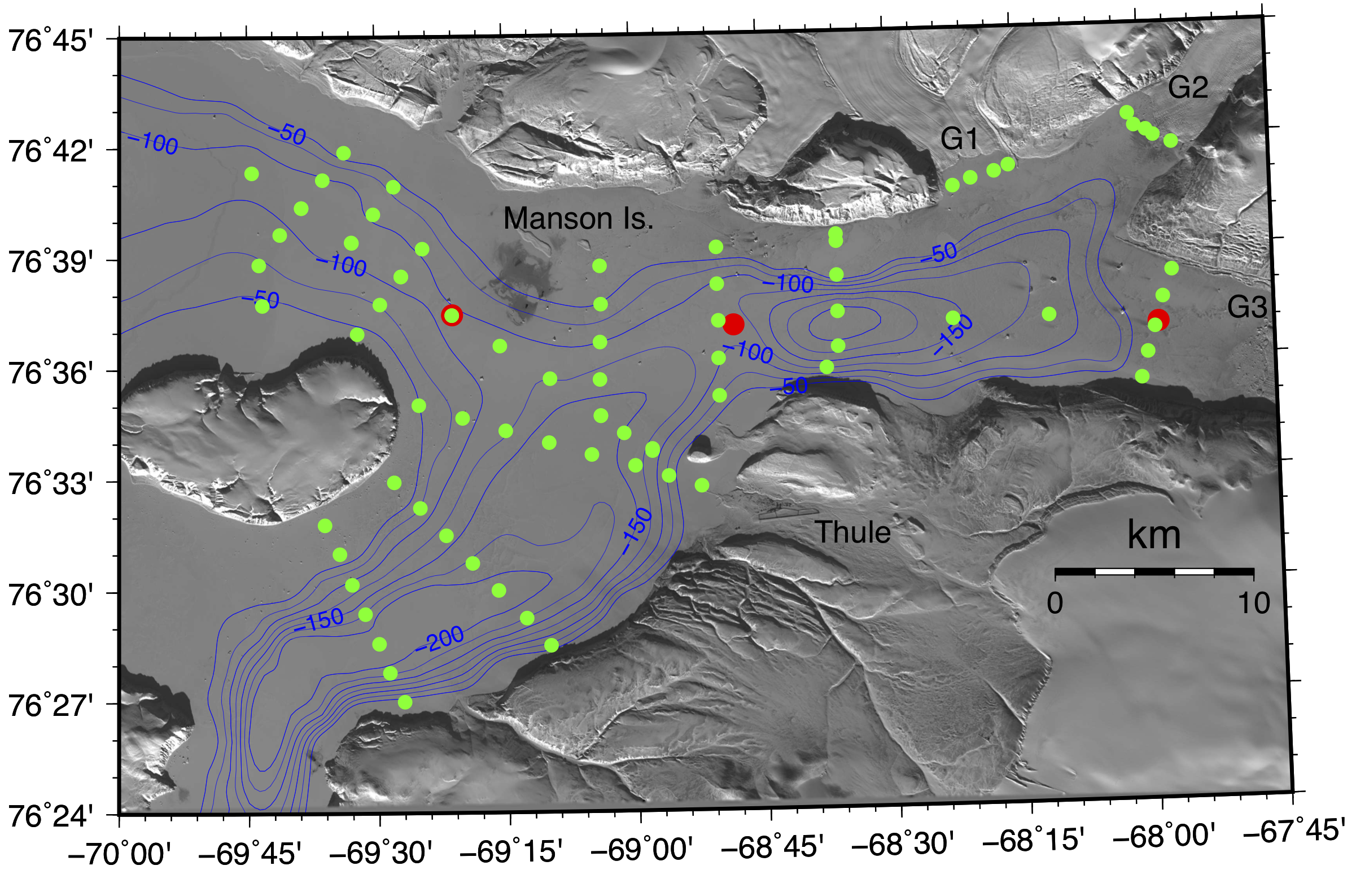

Johnson, H.L., A. Muenchow, K.K. Falkner, and H. Melling: Ocean circulation and properties in Petermann Fjord, Greenland. Journal of Geophysical Research, 116, doi:10.1029/2010JC006519, 2011. .pdf

Muenchow, A., L. Padman, and H.A. Fricker: Interannual changes of the floating ice shelf of Petermann Gletscher, North Greenland, from 2000 to 2012 Journal of Glaciology, 60, doi:10.3189/2014JoG13J135, 2014. .pdf

Muenchow, A., L. Padman, P. Washam, and K.W. Nicholls, 2016: The ice shelf of Petermann Gletscher, North Greenland and its connection to the Arctic and Atlantic Oceans, Oceanography, 29, 84-95, 2016. .pdf

Rueckamp, M, N. Neckel, S. Berger, A. Humbert, and V. Helm: Calving induced speed-up of Petermann Glacier, Journal of Geophysical Research, 124, 216-228, 2019. .pdf

Shroyer, E., L. Padman, R. Samelson, A. Muenchow, and L. Stearns: Seasonal control of Petermann Gletscher ice-shelf melt by the ocean’s response to sea-ice cover in Nares Strait, Journal of Glaciology, 63, doi:10.1017/jog.2016.140, 2017. .pdf

Washam, P., A. Muenchow, and K.W. Nicholls: A decade of ocean changes impacting the ice shelf of Petermann Gletscher, Greenland, Journal of Physical Oceanography, 48, 2477-2493, 2018. source

Washam, P., K.W. Nicholls, A. Muenchow, and L. Padman: Summer surface melt thins Petermann Gletscher ice shelf by enhancing channelized basal melt, Journal of Glaciology, 65, doi:10.1017/jog.2019.43, 2019. .pdf

![IMG_2678 Marine layer at the entrance of Scoresby Sund on Aug.-20, 2018. Photo by Dragonfly Leathrum]](https://icyseas.files.wordpress.com/2019/07/img_2678.jpg?w=330&resize=330%2C220#038;h=220)

![IMG_2642 Fog at noon on Aug.-20, 2018 to the south of Scoresby Sund. [Photo by Dragonfly Leathrum]](https://icyseas.files.wordpress.com/2019/07/img_2642.jpg?w=162&resize=162%2C108#038;h=108)

![IMG_2654 Kap Brewster in the clouds (foreground) at the southern entrance to Scoresby Sund. View is to the north-west into the entrance of the fjord. In the background the northern shores are visible behind the iceberg. [Photo by Dragonfly Leathrum]](https://icyseas.files.wordpress.com/2019/07/img_2654.jpg?w=162&resize=162%2C108#038;h=108)

![IMG_2774 Evening sun on mountains on the Volquart Boons Kyst in Scoresby Sund on August 20, 2018. [Photo by Dragonfly Leathrum]](https://icyseas.files.wordpress.com/2019/07/img_2774.jpg?w=246&resize=246%2C164#038;h=164)

![IMG_2738 Kap Brewster at the southern entrance of Scoresby Sund on Aug.-20, 2018. View is to the south-east out to the open foggy sea. [Photo by Dragonfy Leathrum]](https://icyseas.files.wordpress.com/2019/07/img_2738.jpg?w=246&resize=246%2C164#038;h=164)