Standing on floating Petermann Gletscher last sunday, I called my PhD student Peter Washam out of bed at 5 am via our emergency Iridium phone to check the machine that Keith Nicholls and I had just repaired. We had prepared for this 4 months and quickly established that a computer in Delaware could “talk” to a computer in Greenland to receive data from the ocean 800 m below my feet on a slippery glacier. For comparison the Empire State Building is 480 m high. The closest bar was 5 hours away by helicopter at Thule Air Force Base from where Keith and I had come.

Refurbished ocean observatory linked via cables to a University of Delaware weather station on Petermann Gletscher, Greenland on 28 August 2016. View is to the north.

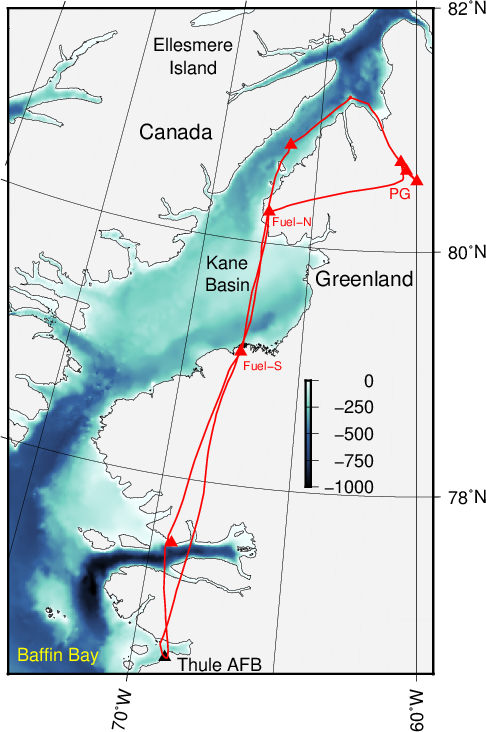

Remote Petermann Gletscher can be reached by helicopter only of one prepares at least two refueling stations along the way. Anticipating a potential future need, we had placed 1300 and 1600 liters of A1 jet fuel at two points from aboard the Swedish icebreaker Oden in 2015. The fuel was given to Greenland Air with an informal agreement that we could use the fuel for a 2016 or 2017 helicopter charter. Our first pit stop looked like this on the southern shores of Kane Basin

Refueling stop on southern Washington Land on 27 August 2016. Air Greenland Bell-212 helicopter in the background, view is to the south towards Kane Basin.

Helicopter flight path on 27/28 August 2016 to reach Petermann Gletscher (PG) via southern (Fuel-S) and northern (Fuel-N) fuel stops in northern Inglefield and southern Washington Land, respectively. Background color is ocean bottom depth in meters.

Upon arrival at the first (northern-most) Peterman Gletscher (PG) station we quickly confirmed our earlier suspicion that vertical motion within the 100 m thick glacier ice had ruptured the cables connecting two ocean sensors below the ice to data loggers above. We quickly disassembled the station and moved on to our central station that failed to communicate with us since 11 February 2016. Keith predicted that here, too, internal glacier motions would have stretched the cables inside the ice to their breaking point, however, this was not to be the case.

My first impression of this station was one of driftwood strewn on the beach of an ocean of ice:

- University of Delaware weather station on Petermann Gletscher on 27 August 2016. View is to the north-east towards the Greenland ice Sheet, that is, the glacier flows from right to left.

- Top section of the University of Delaware weather station on Petermann Gletscher on 27 August 2016. View is to the north-east.

- Bottom section of the University of Delaware weather station on Petermann Gletscher on 27 August 2016. View is to the north-west towards Nares Strait. The palette designed to stabilize the station as the glacier melts under it is turned and rests on the 80 lbs yellow battery box that was strapped to the surface of the palette.

Looks can be deceiving, however, and we found no damage to any electrical components from the yellow-painted wooden battery box housing two 12 Volt fancy “car batteries” at the bottom to the wind sensor on the top. Backed-up data on a memory card from one of two data loggers (stripped down computers that control power distribution and data collections) indicated that everything was working. The ocean recording from more than 800 meters below our feet was taken only a few minutes prior. In disbelief Keith and I were looking over a full year-long record of ocean temperature, salinity, and pressure as well as glacier motions from a GPS. This made our choices on what to do next very simple: Repair the straggly looking ocean-glacier-weather station, support it with a metal pole drilled 3.5 m into the glacier ice, and refurbish the adjacent radar station. We went to work for a long day and longer night without sleep.

Selfie on Petermann Gletscher on sunday 28 August 2016 after 33 hours without sleep. Weather station and northern wall of Petermann in the clouds. It was raining, too.

When all was done, University of Delaware graduate student Peter Washam did the last check at 5:30 am sunday morning. Since then our Greenland station accepts Iridium phone calls every three hours, sends its data home where I post it daily at

The data from this station will become the center piece of Peter’s dissertation on glacier-ocean interactions. Peter was part of the British hot water drilling team who camped on the ice in 2015 for 3 weeks while I was on I/B Oden responsible for the work on the physical oceanography of the fjord and adjacent Nares Strait. Alan Mix of Oregon State University prepared and led the 2015 expedition giving us ship and helicopter time generously to support our work on the ice shelf of Petermann. Saskia Madlener documented the scope of the 2015 work in a wonderful set of three videos

Ocean & Ice – https://vimeo.com/178289799

Rocks & Shells – https://vimeo.com/178379027

Seafloor & Sediment – https://vimeo.com/169110567

A first peer-reviewed publication on this station and its data until 11 February 2016 will appear in the December 2016 issue of the open-access journal Oceanography with the title The Ice Shelf of Petermann Gletscher, North Greenland and its Connection to the Arctic and Atlantic Oceans.

I’m seriously impressed, Andreas. Not just a great job, but I would say heroic.

Thank you for the compliment, but these things always depend on a great many good people … and an element of good luck.

Pingback: What’s happened at Petermann Gletscher since the Industrial Revolution 150 years ago? | Icy Seas