Darkness and cold covers North Greenland, Ellesmere Island as well as Nares Strait, the waterway that connects these two inhospitable places. And despite the darkness of the polar night, I can see that three beautiful arches made of ice connect Greenland to Canada. It is possible to walk across water, if the water is frozen. Stuck to land, ice arches or ice bridges shut down ice motion while the ocean under the ice keeps moving. Lets have a peek at how this looked from space yesterday:

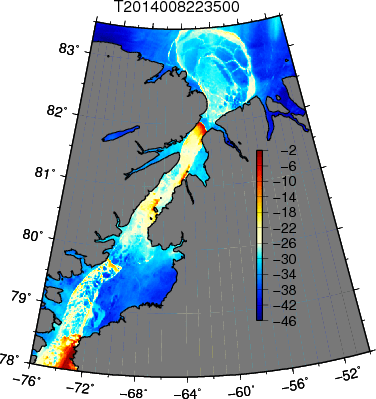

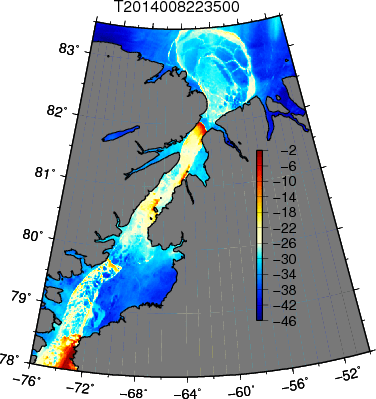

Ice arches of Nares Strait on January 26, 2014 from MODIS thermal imagery. Surface temperatures in degrees Celsius are all below zero despite the missing “-” sign stripped by Adobe Illustrator.

The colors above show the temperature that satellite sensors “see” at the surface of the ice. Red is warm, blue is cold, and grey is land, but “warm” here is still below the freezing point of sea water near -2 degrees Celsius, so even the red or “hot” spots are covered by ice. The 300 deep ocean in Nares Strait generally flows from north to south without trouble under the ice, but just behind the fixed arching ice bridges, it sweeps the newly formed thin ice away to the south. The “warm” spots that form to the south of each ice arches have their own stories:

Farthest to the north a massive ice arch spans almost 200 km (150 miles) across. It faces the open Arctic Ocean to the north and it formed a few days before Christmas 4-5 weeks ago. It was still shedding large ice floes from its edge as it tried, and finally succeeded, I think, to find a stable location. Nevertheless, one of its larger pieces of ice moved into Nares Strait on January-3, 2014 where it became stuck on both Greenland and Ellesmere Islands:

-

-

Jan.-1, 2014

-

-

Jan.-2, 2014

-

-

Jan.-3, 2014

The large floe from the edge of the first ice arch becames firmly lodged on both sides of the 30-km wide entrance to Nares Strait on January-4 (not shown), perhaps aided by strong winds from the north with wind speeds exceeding 40 knots (20 m/s). This second northern arch then aided the formation of the third ice arch in the south. All three arches became first visible on January-8:

Jan.-8, 2014

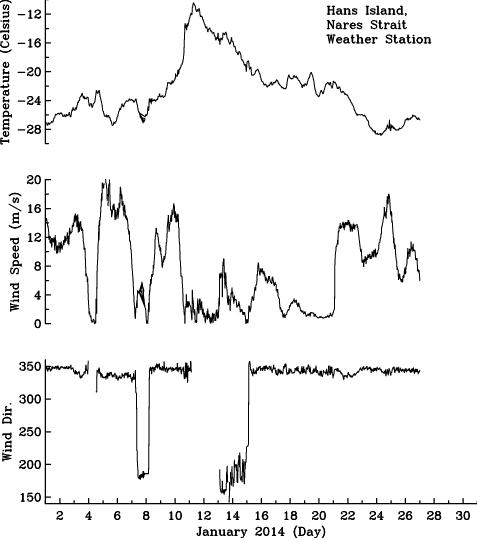

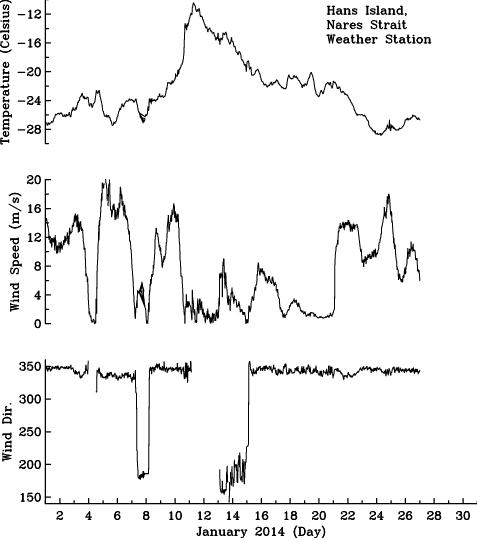

A subsequent lull and short reversal of the winds brought warm southern air masses into Nares Strait while water and drainage pipes froze at my home in Delaware:

Weather record from Hans Island at the center of Nares Strait for January 2014. [Data from Scottish Marine Institute in Oban, Scotland.

“Warm” here refers to -10 degrees Centigrade (+14 Fahrenheit). Air temperatures in Nares Strait today are -21 degrees Celsius (-5 Fahrenheit) while ocean temperatures under sea ice are near -1.8 degrees Celsius (+29 Fahrenheit). It is these “hot” waters that “shine” through the thinner ice as the satellite senses the amount of heat that the ice surface radiates into space. More details on this one finds elsewhere.

I enjoy these elegantly arching ice bridges across Nares Strait, because they challenge me each year anew to question how sea ice, oceans, air, and land all interact to produce them. Nobody really knows. It is a hard problem to model mathematically and many graduate theses will be written on the subject. A student in our own program, Sigourney Stelma, just presented first results and movies of computer simulations of ice bridges forming. Perhaps I can convince her to post some of them on these pages?

Kozo, T.L. (1991). The hybrid polynya at the northern end of Nares Strait Geophys. Res. Let., 18 (11), 2059-2062 DOI: 10.1029/91GL02574

Kwok, R., Pedersen, L.T., Gudmandsen, P. and Peng, S.S. (2010). Large sea ice outflow into the Nares Strait in 2007 Geophys. Res. Let., 37 (L03502) DOI: 10.1029/2009GL041872

Muenchow, A. and H. Melling. (2008). Ocean current observations from Nares Strait to the west of Greenland: Interannual to tidal variability and forcing J. Mar. Res., 66 (6), 801-833 DOI: 10.1357/002224008788064612

0.000000

0.000000