Petermann Gletscher sent off Manhattan-sized islands of ice in 2010 and 2012 that now litter the eastern seaboard of Canada from its farthest northern Ellesmere Island to its farthest eastern Newfoundland. The ice is streaming south along thousands of miles within icy Arctic waters. Petermann Gletscher itself is flat, hard to grasp by the naked eye, its endless expanse of white vanishes into the horizon when we look towards the Greenland Ice Sheet ALONG the glacier:

![North-eastern section of Petermann Glacier on Aug.-11, 2012, the meandering river is the centerline, view is almost due east. [Photo Credit: Canadian Coast Guard Ship Henry Larsen.]](https://icyseas.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/petermannglacier_cghl-360_20.jpg?w=500&h=333)

North-eastern portion of Petermann Glacier on Aug.-11, 2012, the meandering river is the centerline, view is almost due east with Kap Fulford and Kap Agnes on the left center and Daugaard Jensen Land in the background on the right. [Photo Credit: Canadian Coast Guard Ship Henry Larsen.]

Next, lets look ACROSS Petermann from roughly the same latitude. This perspective is more dramatic as vertical cliffs give shape, cliffs are cut by smaller side-glaciers. More specifically, we see the CCGS Henry Larsen helicopter flying down Belgrave Glacier as we look across Petermann which flows from the Greenland Ice Sheet on the left out to sea on the right. On the other (south-western) side we see Faith Glacier in the background about 10 miles away.

![Seaward front of Petermann Glacier Aug.-11, 2012. View is from a small side-glacier towards the south-east across Petermann Fjord with Petermann Gletscher to the left (east). [Photo Credit: Erin Clarke, Canadian Coast Guard Ship Henry Larsen]](https://icyseas.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/p1080580.jpg?w=500&h=375)

Seaward front of Petermann Glacier Aug.-11, 2012. View is from a small side-glacier (Belgrave Gl.) towards a similar glacier (Faith Gl.) across Petermann Fjord with Petermann Gletscher flowing from the left out to sea on the right. [Photo Credit: Erin Clarke, Canadian Coast Guard Ship Henry Larsen]

Contrasting large Petermann Gletscher, the many smaller glaciers on both its sides evoke drama as ice plunges down from 3000 feet above in a rage of forms, colors, and shapes. These side glaciers have their own side glaciers that sometimes rival the Alpine glaciers in Europe, Asia, and the Americas that most of us are more familiar with.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

North-eastern wall of Petermann Fjord in Aug.-2009. [Photo credit: David Riedel, CCGS Henry Larsen]

-

-

Some side glaciers have names, but they are rarely seen on maps and charts. The side glaciers are mapped, but photos are hard to find. Flying over them last year, I was utterly lost. Reviewing photos now, I remember people, smells, computer troubles, and exciting ocean discoveries. Nevertheless, I am hard pressed to place the places we saw on a map or name them. Distances are deceiving, the air is clean and 50-80 miles of visibility are common. A moment later, I cannot see the other side of the ship as we are suddenly in clouds and fog. Everything is always in motion, the ice, the water, the ship, the clouds, all of this without strong reference points like the exit or distance signs on a Turnpike, Interstate, or Autobahn.

![Northern Kennedy Channel near the entrance to Petermann Fjord with Kap Morton in cloud banks. [Credit: Andreas Muenchow]](https://icyseas.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/img_0032.jpg?w=500&h=375)

Northern Kennedy Channel near the entrance to Petermann Fjord with Kap Morton in cloud banks. [Credit: Andreas Muenchow]

And along comes Espen Olsen, a frequent contributor to Neven’s Arctic Sea Ice blog and forums, and discovers a plethora of names that I can check, google, and use to remember expeditions to Petermann over the last 10 years with many good friends. So with his help and that of other explorers like Lauge Koch, Tony Higgins, and the collected wisdom of the U.S. Defense Mapping Agency, I labeled some prominent glaciers and capes on an Aug,-21, 2012 MODIS-Terra image that I constructed from data that NASA provide to anyone free of charge. I chose this image and time, because the 2012 ice island is already in Nares Strait and thus out of sight:

Names of glaciers, capes, islands in Petermann Region over MODIS of Aug.-21, 2012.

Espen tells me that his Danish sources are protected by copyright (I still like to cite them), but the aviation maps of the U.S. military are in the public domain and can be downloaded from the University of Texas in Austin Library, e.g.,

Petermann Gletscher and suroundings extracted from U.S. Defense Mapping Agency Chart ONC A5 (January 1991).

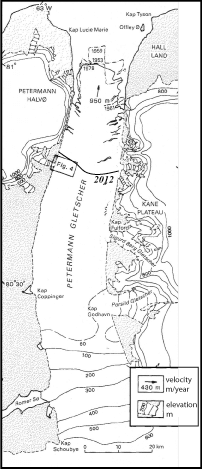

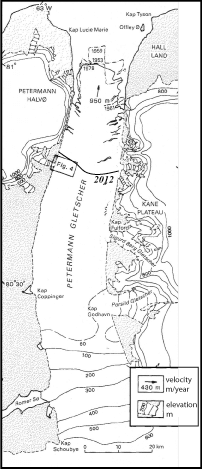

while the modified version of Figure-2 from Dr. Tony Higgins 1990 publication is available at the Alfred Wegener Institute. Nevertheless, it should only be used for non-profit educational purposes or as a reference:

Petermann Gletscher extend and topography from 1953 through 1978 (from Higgins, 1990) with 2012 terminus position drawn in by hand.

With all these details out-of-the-way, we can now start placing photos into places and add names to them. Perhaps others like Espen Olsen can write or edit Wiki entries or correct the false latitude and longitudes that populate the many databases that provide such information on the web. Over the next weeks and months I will try to post as many photos of Petermann’s natural beauty along with an evolving MODIS map that names and shows places. Here are just a few teasers without further comment except what’s in the captions.

![The merging of Sigurd Berg and Hubert Glaciers which discharge into Petermann Gletscher on its eastern wall. The view is landward towards the north-east as the helicopter flies in from Petermann. [Credit: Barbara O'Connell, Canadian Coast Guard]](https://icyseas.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/img_4690.jpg?w=500&h=333)

The merging of Hubert (left) and Sigurd Berg (right) Glaciers which discharge into Petermann Gletscher on its eastern wall. The view is landward towards the north-east as the helicopter flies in from Petermann. [Credit: Barbara O’Connell, Canadian Coast Guard]

![Petermann Gletscher and Fjord in Aug.-2012. View is to the north-west with Faith Glacier (top left) and Kap Lucie Marie (top right) showing the western wall of Petermann. [Photo Credit: CCGS Henry Larsen]](https://icyseas.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/peterman-040.jpg?w=500&h=375)

Petermann Gletscher and Fjord in Aug.-2012. View is to the north-west with Faith Glacier (top left) and Kap Lucie Marie (top right) showing the western wall of Petermann. [Photo Credit: CCGS Henry Larsen]

![Looking down Belgrave Glacier discharging into Petermann Gletscher at its terminus in Aug. 2012 [Credit: CCGS Henry Larsen]](https://icyseas.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/peterman-050.jpg?w=500&h=375)

Looking down Belgrave Glacier discharging into Petermann Gletscher at its terminus in Aug. 2012 [Credit: CCGS Henry Larsen]

Higgins, A.K. (1990). Northern Greenland glacier velocities and calf ice production Polarforschung, 60, 1-23 Other: 0032-2490

![An F-102 jet of the 332d Fighter-Interceptor Squadron at Thule AFB in 1960. [Credit: United States Air Force]](https://icyseas.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/332d_fighter-interceptor_squadron_-_f-102_-_thule_ab.jpg?w=500&h=249)

![Ice fields seen in Labrador Current April 6, 2008 from a plane. [Photo Credit: Daniel Schwen]](https://icyseas.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/labrador_current.jpg?w=500&h=333)

![North-eastern section of Petermann Glacier on Aug.-11, 2012, the meandering river is the centerline, view is almost due east. [Photo Credit: Canadian Coast Guard Ship Henry Larsen.]](https://icyseas.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/petermannglacier_cghl-360_20.jpg?w=500&h=333)

![Seaward front of Petermann Glacier Aug.-11, 2012. View is from a small side-glacier towards the south-east across Petermann Fjord with Petermann Gletscher to the left (east). [Photo Credit: Erin Clarke, Canadian Coast Guard Ship Henry Larsen]](https://icyseas.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/p1080580.jpg?w=500&h=375)

![Northern Kennedy Channel near the entrance to Petermann Fjord with Kap Morton in cloud banks. [Credit: Andreas Muenchow]](https://icyseas.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/img_0032.jpg?w=500&h=375)

![The merging of Sigurd Berg and Hubert Glaciers which discharge into Petermann Gletscher on its eastern wall. The view is landward towards the north-east as the helicopter flies in from Petermann. [Credit: Barbara O'Connell, Canadian Coast Guard]](https://icyseas.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/img_4690.jpg?w=500&h=333)

![Petermann Gletscher and Fjord in Aug.-2012. View is to the north-west with Faith Glacier (top left) and Kap Lucie Marie (top right) showing the western wall of Petermann. [Photo Credit: CCGS Henry Larsen]](https://icyseas.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/peterman-040.jpg?w=500&h=375)

![Looking down Belgrave Glacier discharging into Petermann Gletscher at its terminus in Aug. 2012 [Credit: CCGS Henry Larsen]](https://icyseas.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/peterman-050.jpg?w=500&h=375)

![The evolution of Jacobshavn Isbrae retreat from 1851 through present. [From NASA's Earth Observatory]](https://icyseas.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/jakobshavn_retreat-1851-2006.jpg?w=500&h=375)