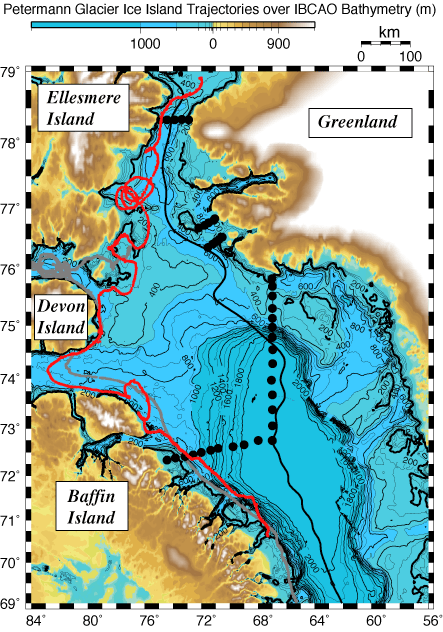

The BBC keeps asking good and penetrating questions about the fate of Greenland’s many icebergs in general and Petermann Glacier’s Ice Island in particular. A poor telephone connection across the Atlantic this morning prevented an interview, but made me answer a number of questions in writing. When answering these questions, I was thinking of those icebergs and ice islands one finds in abundance in the frigid waters of Baffin Bay, the Labrador Sea, and next to Greenland. I am not talking about what happens once icebergs enter the subtropical Atlantic Ocean and meet the Gulf Stream to the south of the Grand Banks, that is a different story.

USCG Healy besides massive iceberg in northern Baffin Bay, July 2003

1. What can icebergs tell us about oceans?

Icebergs are particles that track averaged ocean currents over the top 200-m or so. These currents are often refered to as “geostrophic” currents which is really a different word for an ocean force balance between pressure gradients (estimated from measurements of temperature and salinity changes with depth at many locations) and the Coriolis force due to the earth’s rotation. This is why RADM Edward H. “Iceberg” Smith of the US Coast Guard spent so much time sailing and taking measurements off northern Canada in the 1920ies and 1930ies as part of the International Ice Patrol. His outstanding publications 80 years old are a first example on how to apply theory (the Scandinavian or Bergen School of the 1920ies regarding dynamical physical oceanography) to a very specific application.

2. How does the trajectory of the ice-islands/ and other icebergs show information about the ocean currents?

Ice islands and icebergs are thick (50-200 m) and mostly submerged below the surface. Hence they are largely moved by the ocean currents about 30-200 m below the surface. I think of them as ocean drifters with a very large and deep drogue element that changes with time as the iceberg melts or tips over. This is different from sea ice that may reach only 5-m into the water column and thus only “sees” the very surface layer of the ocean that is largely influenced by winds. This is not entirely true for icebergs, because they are driven by ocean currents below the thin (10-20 m) ocean “mixed layer” that sea ice is embedded in.

3. What are the current unknowns or poorly understood parameters with regards to iceberg science and iceberg interactions with oceans in the High Arctic?

I think the problem with any prediction scheme of individual particles is that the ocean always has a strong turbulent and unpredictable part to it. This problem is fundamentally no different from trying to predict where oil from a spill will come ashore. We can do it “on average” rather well, but we are very poor trying to do in one specific case for a specific iceberg (or spill). Oh, this certainly also applies to climate predictions, easy to do “on average,” very hard to do in a specific case for a specific time and place that may be affected.

4. What sort of temperatures would the water be?

Meltwater plumes at zero salinity with pieces of ice floating in it have a temperature of 0 C, meltwater plumes with pieces of ice in it at ocean salinities have temperatures of about -1.8C, depending on the amount of sunlight and how much mixing takes place, these fresh and very thin surface layers (1-10 meters) can heat up substantially fast, and cool just as fast. In June/July you have 24 hours of sunlight, so temperatures of 4-10 C are not out of the ordinary, but these waters will do very little melting, because most of the mass is well below a 10 m depth of such fresh surface plumes.

Temperature (left) and salinity (right) distribution off Labrador in the summer of 2009 with depth and distance from the coast (from Colbourne et al., 2010). Note the very cold waters near the freezing point (blue and purple) on the continental shelf below 50-m depth.

5. How would changes in ocean stratification and temperature alter the melting of icebergs?

First, ocean temperature (or heat) and stratification are two very different things. In the Arctic almost all stratification is done by salinity, temperature is a tracer that has very little effect on density stratification. This is also the reason, that most of the ocean’s heat in the Arctic is at depths 200-400 m below the surface. This warm water does NOT rise towards the surface, because it is also salty water, it is often refered to the Atlantic Layer. This deep reservoir of heat is what many oceanographers (myself included) have in mind when they talk about the melting of Greenland’s glaciers by the ocean from below.

Petermann Glacier, for example, has a grounding line at 600-m below the surface. This grounding line is in contact with the heat from the Atlantic Layer that is melting it, but the melted water is fresh and cold, immediately stratifying the water column under the ice, so a source of energy is needed also to move or mix this cold fresh melt water away. An inclined slope may do so, tides may do so, internal waves traveling and breaking on the interface between cold-fresh and warm-salty waters may do so. At Petermann Glacier this Atlantic layer does not reach most of the floating element of this glacier, because it is only 100-200 m thick and thus does not extend into the heat of the Atlantic Layer. So, vertical stratification and location of heat are two different things.

Breaking waves on an interface due to a shear instability, i.e., flow in the (fresh and cold) upper layer is less than the flow in the denser (warm and salty) lower layer.

Second, think of ocean stratification as a blanket that insulates one region from the other. Removing the blanket requires kinetic energy (something or someone has to do the work, doing work requires energy). As you melt freshwater ice via conduction of heat to the ice, the melt has zero salinity and a temperature at the freezing point. This zero salinity water acts as the insolation blanket that reduces the heat reaching the ice. So, again, you need (a) a source of kinetic energy to do work to break down the stratification (of salinity) to (b) enable the transfer of heat from the ocean to the ice.

6. Can you recommend any key journal papers you think we should read?

The classical paper on this subject is [Gade, H.G., 1979: Melting of ice in sea water: A primitive model with application to the Antarctic Ice Shelf and Icebergs. J. Phys. Oceanogr., 9, 189-198], but this paper is a thorough theoretical development. I have professors of glaciology asking me what it means, so the material is not easy to penetrate. In a 2011 publication on the oceanography of Petermann Fjord impacting this Glacier, we made extensive use of the arguments and concepts presented in Gade (1979). That publication is more readable and accessible.

Its first author is Dr. Helen Johnson at Oxford University with whom I have collaborated since 2003 aboard US and Canadian icebreakers. She also published an illustrated diary of our 2007 expedition to Nares Strait.

ADDED Jan-12: My mind yesterday was unclear on the in situ temperature at which glacier ice of zero salinity is melting in seawater such as found on the Labrador shelf. The comment below points this out concisely, while this link to TheNakedScientist perhaps provides the longer and more visual explanation. Another fun explanation of the melting and freezing of ice in a salt solution relates to the making of ice cream. A subsurface temperature at -1.5 C at a salinity of 33.5 psu such as found on the Labrador shelf does melt the zero salinity ice of the iceberg somewhat. A boundary layer consisting of fresh meltwater will lower the salinity adjacent to the iceberg which will increase the freezing point which will reduce the melting until a new stable equilibria is reached.