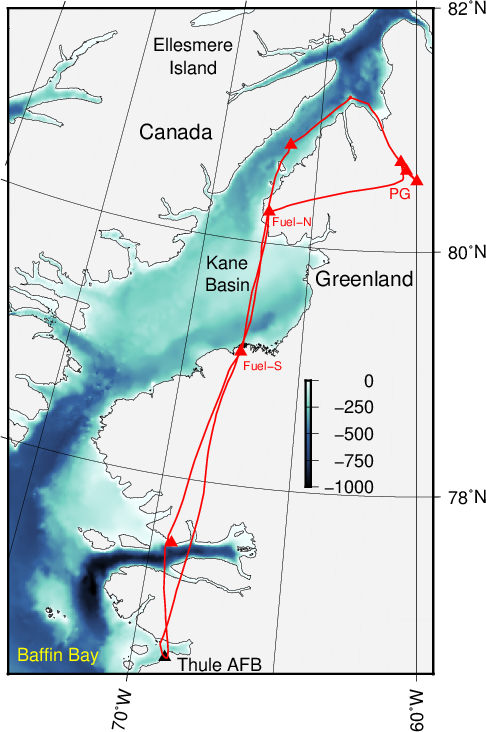

Where to land a plane in North Greenland? This remote wilderness has the last floating ice shelves in the northern hemisphere such as Petermann Gletscher. Two weeks ago Dr. Keith Nicholls of the British Antarctic Service (BAS) and I visited this glacier to fix both ice penetrating radars and ocean moorings that we had deployed in 2015 after drilling through more than 100 meters of glacier ice. The BAS radars measure how the ice thins and thickens during the year while my moorings measure ocean properties that may cause some of the melting. Keith and I are thinking how we can design an experiment that will reveal the physics of ocean-glacier interactions by applying what we have learnt the last 12 months. First, however, we need to figure out where to land a plane to build a base camp and fuel station in the wilderness.

I searched scientific, military, and industry sources to find places where planes have landed near Petermann Gletscher. The first landing, it seems, was a crash landing of an US B-29 bomber on 21 February 1947 at the so-called Kee Bird site. All 11 crew survived, the plane is still there even though it burnt after a 1994/95 restoration effort that got to the site in a 1962 Caribou plane landing on soft ground with a bulldozer aboard that is still there also. A Kee Bird forum contains 2014 photos and, most importantly for my purpose, a map.

![Location of Kee Bird and other landing sites in North Greenland near Petermann Gletscher. [From Forum]](https://icyseas.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/2014_washingtonland_map.jpg?w=500&h=346)

Location of Kee Bird and other landing sites in North Greenland near Petermann Gletscher. [From Michael Hjorth]

Michael Hjorth posted the map after visiting the region as the Head of Operation of Avannaa Resources. This small mineral exploration company was searching for zinc deposits and was working out of a camp a few miles to the north of the Kee Bird site and a few miles to the west of Petermann Gletscher. The Avannaa Camp was on the north-western side of an unnamed snaking lake in a valley to the south of Cecil Gletscher, e.g.,

Here are videos that show Twin Otter, helicopter, and camp operations all at the Avannaa site in 2013 and 2014:

The Avannaa camp of 2013 and 2014 was supplied from a more southern base camp at Cass Fjord that Avannaa Logistics and/or another mineral company, Ironbark.gl apparently reached via a chartered ship.

Cass Fjord Base Camp on southern Washington Land and Kane Basin. Credit: IronBark Inc.

A summary of all 2013-14 Washington Land activities both at the Avannaa Camp next to Petermann Gletscher and the Cass Fjord Base Camp adjacent to Kane Basin is contained within this longer video of Michael Hjorth

The mining explorations are based on geological maps that Dr. Peter Dawes of the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland provided about 10-20 years ago. These publications contain excellent maps and local descriptions both of the geology and geography of the region as well as logistics. The perhaps most comprehensive of these is

Click to access map1_p01-48.pdf

from which I extract this map that shows both the Cass Fjord and Hiawatha Camps:

Dawes (2004): “Simplified geological map of the Nares Strait region …” from Thule Air Force Base in the south to the Arctic Ocean in the north with Petermann Gletscher in the center of the top half.

while

Click to access gsb186p35-41.pdf

has this photo on how one of these landing strips looks like on a raised beach

If we do plan future activities at Petermann Gletscher and/or Washington Land and/or areas to the north, then I feel that the Avannaa site may serve as a good semi-permanent base of operation for several years. It is here that Ken Borek Twin Otter landed several times. It is reachable with single-engine AS-350 helicopters that could be stationed there during the summer with a fuel depot to support field work on the ice shelf of Petermann Gletscher and the land that surrounds it. The established Cass Fjord Base Camp to the south would serve as the staging area for this Petermann Camp which has both a short landing strip suitable for Twin Otter and potential access from the ocean via a ship. Access by sea may vary from year to year, though, because navigation depends on the time that a regular ice arch between Ellesmere Island and Greenland near 79 N latitude breaks apart. There are years such as 2015, that sea ice denies access to Kane Basin to all ships except exceptionally strong icebreakers such as the Swedish I/B Oden or the Canadian CCGS Henry Larsen. In lighter ice years such as 2009, 2010, and 2012 access with regular or ice-strengthened ships is possible as demonstrated by the Arctic Sunrise and Danish Naval Patrol boats. International collaboration is key to leverage multiple activities and expensive logistics by land, air, or sea in this remote area of Greenland.

![Swedish icebreaker I/B Oden 22 July 2015 on its way to Thule. [Photo Credit: https://twitter.com/SjoV_isbrytning]](https://icyseas.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/ckhcffzxaaadzhh.jpg?w=500&h=375)