I go to sea to learn about oceans, glaciers, weather, and climate. Despite dramatic photos of exciting field work, those action-packed scenes or serene nature shots of beauty and violence are misleading. Most of my time is spent sitting an a desk in a spacious office with books, papers, telephone, and most important of all, my computers.

- Selfie at my office desk

- Books and expedition notes.

- Corner of my office desk.

Most of my time is spent writing. The writing is varied and ranges from illustrated essays on IcySeas.org to computer code. Add technical writing of research proposals, papers, and reviews for funding agencies and scientific journals. My screen rarely looks like what is shown above with the beautiful LandSat image of 79N Glacier as a screen-saver, it actually looks like this

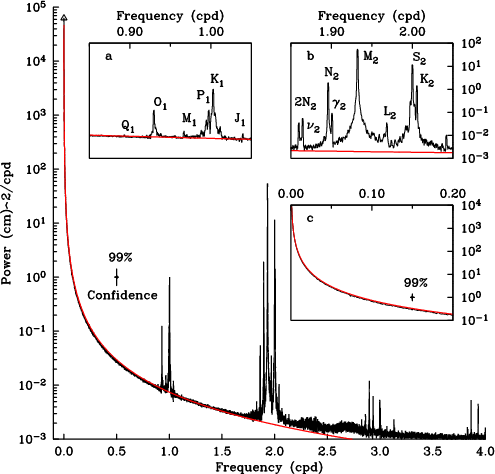

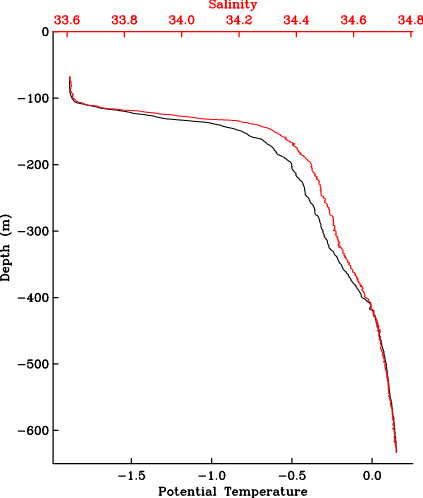

The blog-writing window is open on the right while a Fortran computer code is in the top left. The code processes temperature, salinity, and pressure data from Petermann Glacier. When the code is run in the bottom-left window, it produces numbers. In this specific case, the numbers are from the only profile of temperature and salinity that exists from Petermann Glacier. Koni Steffen collected the data in 2002. Columns are depths that start at -68 (meters), salinity at 33.774 (no units, think of this as grams per kilogram), temperature at -1.885 (degrees centigrade), and the last column is the density anomaly These numbers are better presented as a graph:

Notice that temperature and salinity start only at -68 meters. This is because the ice at this location was about 68-m thick. The Big Ben clock in London is about 96-m high, but this piece if Petermann was chosen because it was less hard to drill through 2/3 of Big Ben’s height when compared to drilling through the glacier ice a mile away where the ice is thicker than the Empire State Building in New York; but I digress.

The profile above reveals a pattern we find almost anywhere in deeper Arctic Waters: Temperature increases with depth. Under the ice at 68-m depth, water is at its freezing point. As you move down the water towards the bottom, salinity increases and so does temperature. It is still cold, about +0.2 degrees Celsius, but this is heat from the North Atlantic Ocean that for perhaps 20-50 years circled all the way around the Arctic Ocean from northern Norway, past Siberia, past Alaska, past Canada to reach this spot of Greenland. While this appears marvelous, and it is, this is NOT what gets a physical oceanographer excited, but this does:

It is the same data, but I did some reading, physics, algebra and code-writing in that order. First, instead of temperature, the blue line shows the difference between temperature T and the temperature Tf above the freezing. The difference T-Tf relates to the amount of heat available to melt the ice somewhere. The black line is the real killer, though. It combines salinity and temperature observations to reveal where the glacier water resides at this location that was melted somewhere else. Without going into the physical details, glacier meltwater is present where the black line touches zero (the so-called Gade-line, so named after a Swedish oceanographer who proposed its use in 1979). This happens at a depth from about 280-m to 500-m depth. This means that the glacier is NOT melting where it is as thin as Big Ben, but instead where it is as thick as the Empire State Building. So this is where we will need to place our instruments.

Proving my initial point, I spent two hours of fun writing this blog. I now will have to focus on more technical writing to pay the many bills of sea-going research. These “lab-notes” also serve as a document to raise $10,845 to install instruments this summer through Petermann Gletscher, have a look and give a little, if you can at

https://experiment.com/projects/ocean-warming-under-a-greenland-glacier

![Seaward front of Petermann Glacier Aug.-11, 2012. View is from a small side-glacier towards the south-east across Petermann Fjord with Petermann Gletscher to the left (east). [Photo Credit: Erin Clarke, Canadian Coast Guard Ship Henry Larsen]](https://icyseas.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/p1080580.jpg?w=500&h=375)