[Editor’s Note: Undergraduate Julie Jones of the University of Delaware summarizes her work that was supervised by Helga Huntley as part of an NSF-funded summer internship.]

Three years ago in 2009 Andreas Muenchow left from Delaware for Greenland with students Pat Ryan and Berit Rabe to recover instruments that recorded salinity, temperature, current velocities, and ice thickness in Nares Strait since 2007. This summer, I used those observations to estimate ice thickness for April through June in 2008 and compare them to estimates for the same spring period in 2009. An ice bridge had formed in 2008 but not in 2009. Working as a group, we wanted to investigate the effect of ice arches on the ice thickness. Allison Einolf, another summer intern who focused on ocean currents during the same time periods and Andreas produced these maps that introduce the study area, spatial ice cover, and mean ocean currents:

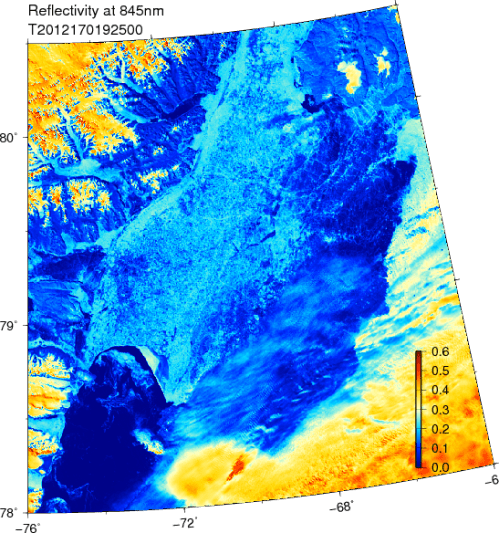

Nares Strait MODIS satellite imagery of the study area and ice arch April 21, 2008. Red dots are instrument locations. Arrows show current velocities.

Nares Strait MODIS satellite imagery of the study area and ice arch April 22, 2009. Red dots are instrument locations. Arrows show current velocities. Note the lack of the southern ice arch, but the presence of one north of the study area.

I used Matlab for most of the data processing, more specifically the Ice Profiling Sonar (IPS) Processing Toolbox for Matlab provided by the manufacturer of the instrument that collected the data: ASL Environmental Sciences, Inc. First I transformed the data from the IPS instrument into a range time series. I then manually “despiked” the data, taking out any data points that were likely due to bubbles or fish within the acoustic path from the sensor system to the ice above and back. In a second step I wrote a function using sound speed data from Andreas, atmospheric pressure from Dr. Samelson at Oregon State University, and pressure (depth) data from the IPS instrument to get a time series of the thickness of the ice. In a third step I applied a Lanczos raised cosine filter that was taught as part of a 2012 Summer Intern Page Workshop. Hence I finally had some nicely filtered data for the periods of the April-June of 2008 and 2009.

Now the results: Just as we expected, there was much thicker ice in the 2008 spring with a southern ice arch present than there was in the spring of 2009 when no such ice arch was present:

Histogram for April – June 2008 ice. There is a peak at 3 meters, with almost 25% of the ice that thick.

Histogram for April – June 2009 ice. The ice does not get thicker then 2 meters with most of the ice thinner than one meter.

The histograms show thicker ice in 2008, about 2-6 meters on average and with some ice even reaching 10 meters. In 2009, the ice doesn’t get thicker than 2 meters with most of the ice being thinner than 1 meter. More specifically, the mean ice thickness for April – June 2008 (2009) is 3.8 (0.58) meters with a standard deviation of 1.8 (0.29) meters. This further shows that there was thicker ice in 2008 than there was in 2009. I attributed the cause for the thin 2009 ice to ice flowing freely through Nares Strait all winter and spring as no ice arch in the south blocked such flow. The ice, thus, did not spend enough time in the high Arctic to thicken.

I noticed something else in my histograms when the 2008 ice bridge collapsed.

The monthly histograms show that the ice in April and May is thicker than the ice in June. We know that the 2008 ice bridge collapsed near June 6th, so it is interesting and it makes a lot of sense that the ice in June would be thinner than the ice two months earlier.

The mean ice thickness for April 2008 was 4.6 meters with a standard deviation of 2.40 meters. In May 2008 the mean ice thickness was 3.5 meters with a standard deviation of 1.40 meters. Lastly, in June the mean ice thickness was 3.5 meters with a standard deviation of 1.30 meters. The ice thickness decreased after April and the variability decreases in June, which helps detect the bridge collapse in the data.

Lastly here are the filtered time series of April – June of 2008 and 2009.

Filtered time series for April – June 2009 with a different scale to see the variability over time more clearly.

Hopefully we can see more interesting and exciting results from the instruments that the Nares Strait team picked up this summer even though they were hit hard by the 2010 Petermann Ice Island!