A new ice island separated from Petermann Glacier on July 16, 2012 as reported here first. Less than 4 weeks later, the Canadian Coast Guard Ship Henry Larsen reconnoitered the ice island on Aug.-9 when it blocked the northern half of the entrance of the fjord.

Petermann Ice Island 2012 (PII-2012) as seen Aug.-11, 2012 at the entrance of Petermann Fjord. The view is to the north-west. [Photo Credit: Canadian Coast Guard Ship Henry Larsen.]

I was aboard this ship when Captain Wayne Duffett decide to break into the largely ice-free fjord behind the ice-island after consultations with Ice Services Specialist Erin Clarke. The ice observer had just returned from her second helicopter survey in 2 days with pilot Don Dobbin to assess both ice cover and its time rate of change. From the time the ship entered the fjord behind the ice island, hourly flights to a fixed point at the south-western corner of the ice island ensured that its movement would not cut off the ship’s exit. This approach worked and it gave the science crew of 8 aboard about 18 hours to conduct the very first survey of a previously ice-covered ocean:

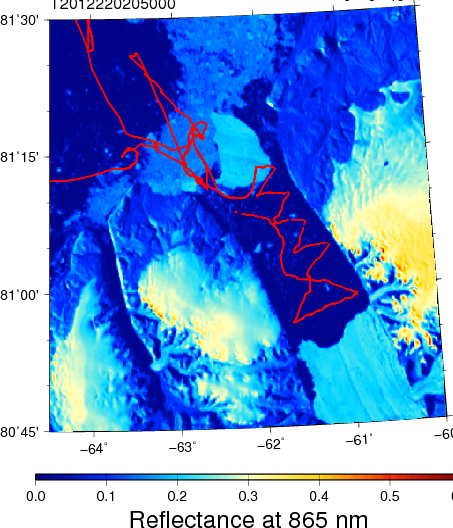

Petermann Glacier, Fjord, and Ice Island as seen by MODIS at 865 nm on Aug. 07, 2012 overlaid with survey lines of CCGS Henry Larsen on Aug.-9/10/11, 2012 in red.

We were not funded to do enter the fjord, but our main mission to recover an array of ocean moorings with 3-year long data records covering the 2009-12 period about 100 km to the south in Nares Strait has already been accomplished. So, what does a physical oceanographer do when in uncharted and unknown territory? He drops a number of CTDs, that is, measuring conductivity (C), temperature (T), and depth (D, pressure, really) as the instrument (the CTD) is lowered at a constant rate from the surface to the bottom of the ocean at a number of stations. The results from such work next to the present front of Petermann Glacier was a surprise for which we do not yet have a satisfactory explanation: The waters inside the fjord are much warmer at salinities 32.5-34.25 than they are outside the fjord:

Temperature as a function of salinity from 9 stations across Petermann Fjord next to the current seaward edge of Petermann Glacier on Aug.-10, 2012 in red. For comparison I show in blue a station done outside the fjord on Aug.-9, 2012. Note that temperatures increase with increasing salinity which is expected for waters that are a mixture of cold and fresh polar and saltier and warmer Atlantic waters. Density deviations from 1000 kg/m^3 are shown as solid contours along with the freezing temperature that decreases with increasing salinity.

Another way to show the same data is to actually plot the section, that is, the distribution of temperature and salinity in physical space across the fjord as a function of depth:

Section across the seaward edge Petermann Glacier on Aug.-10, 2012 for salinity (left panel) and temperature (right panel). Symbols indicate station locations from which color contours are drawn. Note that the display is cropped to the top 300 meters while real recordings extend to the bottom which exceeds 1000 meters. The view is eastward towards the glacier with north to the left.

Note the doming salinity contours which to classically trained oceanographers suggest a flow out of the page on the right and into the page on left with maximum at about 90 meter depth relative to no flow at, say, 500 meter depth. Another way to view this distinct property distribution is that the flow above 90 meters is clockwise (outflow on left, inflow on right) relative to the more counter-clockwise flow below this depth. This feature, too, comes as a surprise and requires more thought and analyses to explain.

There is much more work to be done to figure out what all this means. I feel like scratching the surface of a large iceberg half-blind. The data from below 300 meter depth, too, contain clues on how some this glacier interacts with the ocean. As for the purpose of this post, I merely wanted to report that the ice island is presently having a hitting or scratching tiny Hans Island. The latter is unlikely to move, but Petermann’s Ice Island will slow on impact, swivel counter-clockwise, bump into Ellesmere, and pretend nothing has happened on its merry way south. This is the latest image I have:

Petermann Ice Island 2012 on Aug.-22, 2012 as seen by MODIS Terra at 21:45 UTC. The tiny red dot marks Hans Island, the location of a weather station in the Kennedy Channel section of Nares Strait. Petermann Fjord is towards the top right out of view.

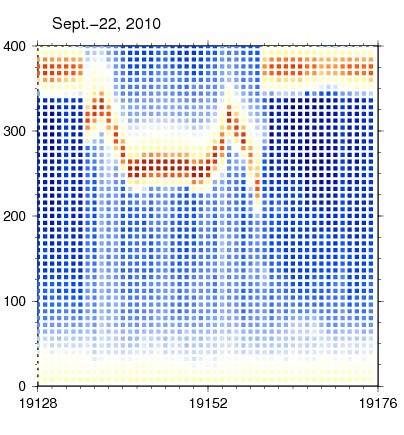

ADDENDUM Sept.-1, 2012: PII-2010B had a maximum thickness of at least 144 meters as it passed over a mooring that measures ocean currents from the Doppler shift of acoustic backscatter that is shown here for one of four beams:

Time-depth series of acoustic scatter from a bottom-mounted acoustic Doppler current profiler for 24 hours starting Sept-22, 2010 9:30 UTC. Red colors indicate high backscatter from a “hard” surface like ice. The vertical axis depth in meters above the transducers while the horizontal is ensemble number into the record (0.5 hours between ensembles). The 2010 ice island from Petermann Glacier (PII-2010B) passed over the mooring. When PII-2010B was attached to the glacier it was adjacent to the segment that became PII-2012 this year.