Pavla stopped her Suburu Outback on the side of the road in Tuoloume Meadows, Yosemite National Park to pick up a 63-year old hitchhiker who tried to reach his remote Parker/Mono trailhead. First, however, Pavla had to take a swim in the wild local river. Thus she provided the aging back-packer, that was me, with an expert lesson on what to do in California’s back-country when one sees a pristine lake or stream: undress and jump in. And so I did with some hesitation, admittedly, the water was cold after all. Jumping naked into a stream after an attractive woman who had just picked me up from the side of a road, I do not do that naturally, but Pavla taught me how to swim in places like these:

Minaret reflections in Ediza Lake (top left, Aug.-13), Western Cedar tree along the way (top right, Aug.-13), Rush Creek (bottom, Aug.-11), and Rosalie Lake (right center, Aug.-13).

I swam the next 14 days in Rush Creek, Emerald Lake, Ediza Lake, Shadow Lake, Rosalie Lake, McCloud Lake, Duck Lake, Purple Lake, Lake Virginia, Big McGee Lake, Fourth Recess Lake, Pioneer Lake-10817, Pioneer Lake-10871, Pioneer Lake-11194, and lastly Trail Lake. And at each of these daily swims I was alone in or at the water. Only McCloud Lake I shared with two anglers early in the morning, but this lake was about 1/2 mile from the bus stop to the town of Mammoth Lakes, California, where I resupplied myself with food a week into my hike. Passing over Duck Pass the next day, I was now on my way towards Pioneer Basin which was the main goal of this years’ trip into mountains.

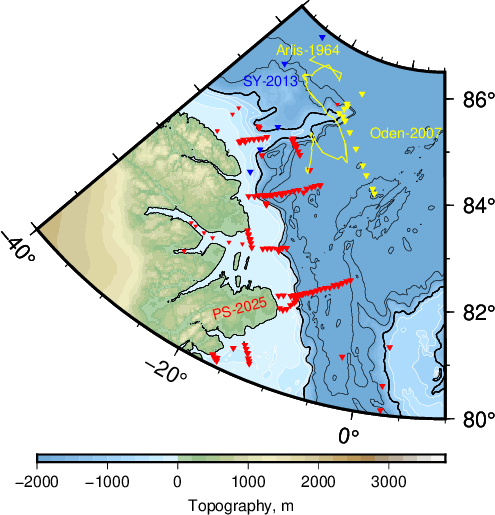

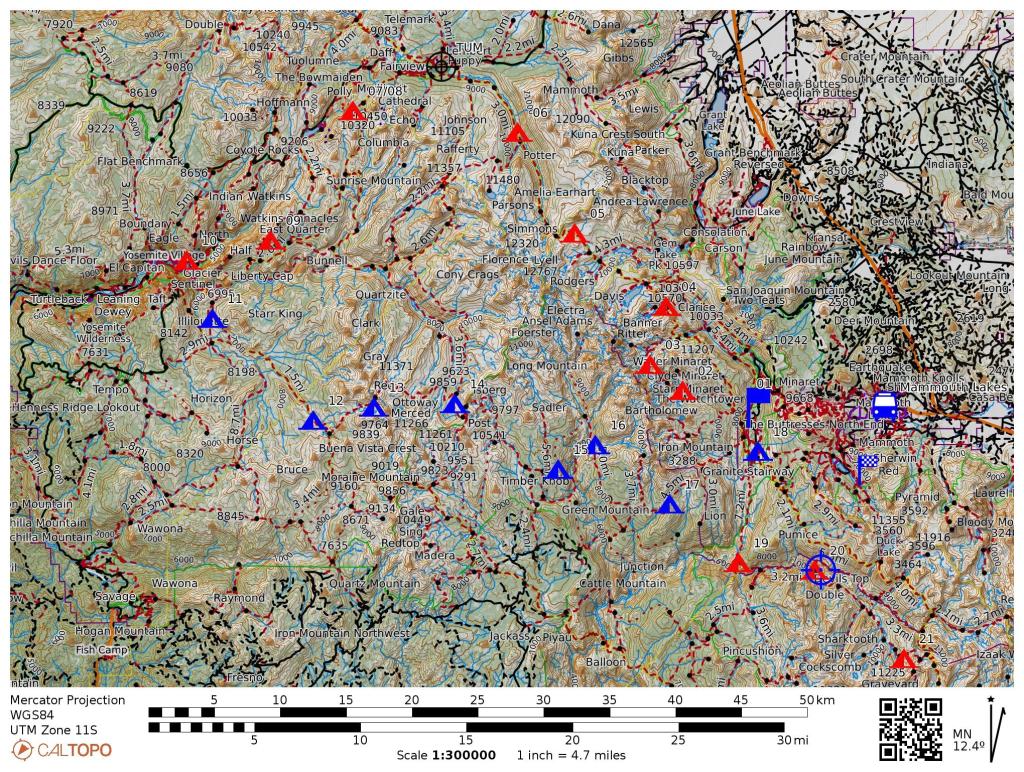

Tracks, camps, and swims during 2025 back-packing trip Aug. 9-22. Flags indicate trailheads with entry in Yosemite National Park in the north (blue track) and John Muir Wilderness in the south (red track). Crosshairs are at Kuna Mountain (13,008′ or 3965 m) in the north and Red Slate Mountain (13,135′ or 4002 m) in the south. Right panel is a close up of McGee Pass, Red Slate Mountain, Hopkins Pass, and Pioneer Basin.

Pavla encouraged me to get into Pioneer Basin which she described as a wild, beautiful, and flatish place with many lakes and no trails. And so it was my home for 3 days and nights. The lack of trails scared me at first, because my 2024 California hike challenged me when my trail disappeared for 3 days in Ansel Adams Wilderness. The “trail” was there in theory, but it was overgrown by waist high brush, young trees, leave piles, and fallen trees after several forest fires raged through the area 10 or 20 years ago. This was at lower altitudes of 7,500′ (2300 m) and thus well below the treeline. In contrast, Pioneer Basin is above the treeline near 11,000′ (3300 m) and surrounded on 3 sides by high mountains to ease navigation. Nevertheless, it was tricky to reach from the north-west, because I had to cross two high passes only one of which had an established trail.

McGee Pass came first after hiking down to and then up Fish Creek to its origin below the snow fields of Red Slate Mountain. I hiked loosely with two parents my age and their grown two daughters and their dog. I had met them 3 days prior climbing up to Duck Lake and we kept meeting each other on the trail with few other people. We had lunch together atop McGee Pass at 11,900′ (3600 m) when I decided to climb the mountain following yet another tip of Pavla. Without my backpack the climb up Red Slate Mountain was at first delightful, but later became steep and strenuous. Much to my surprise, I suddenly had cell phone coverage near the top and I sent photos to my wife Dragonfly back home. It felt strange and funny to sit atop high mountains talking to Dragonfly who was walking below tall skyscrapers near Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue. She was not eager to talk, because she tried frantically to escape rain and traffic with a group of friends. Her husband, meanwhile, sits mellow atop the worlds with nearby clouds and far horizons as his only companions:

Lunch at McGee Pass (top left) and views from Red Slate Mountain towards Red and White Mountain (top right), towards north into Yosemite (center right), and towards south (bottom). The bottom photo shows three lakes with a faint path on the left and a zig-zag path up to McGee Pass on the right. The mountains in the far back are Mills, Abbott, and Dade Mountains that merge together at the end of the long ridge that bounds Fourth Recess. I crossed all these ranges the next 5 days to exit via Mono Pass to the east (left) of Fourth Recess. Hopkins Pass crosses the lower center ridge near a triangular snow patch. Pioneer Valley is to the left (outside frame) of the wooded Hopkins Valley. [Aug.-17, 2025.]

When I came down the mountain and reached my campsite at the lowest lake in the photo above (Big McGee Lake) it was 7 pm. I met my earlier hiking companions, told them about my adventures atop the mountain, and went for a swim just as the sun set for the day. I slept well that night, but got up early to climb over Hopkins Pass along a sketchy, barely existing path. Detailed descriptions of the route I found in Backpacking from McGee Creek to Pioneer Basin via Hopkins Pass by Inga Aksamit. She also moderates an outstanding Facebook group on the John Muir Trail that I used for my 2024 backpacking trip. Thanks to this guide the crossing of Hopkins Pass went well. It included an almost vertical scramble up a cliff on all fours to reach a tiny ice cap near the top.

The last 400′ (120 m) of Hopkins Pass at 11,470′ (3500 m) up a bouldery cliff with a snow wedge above (left) along with views from the top such as Red and White Mountain (top right) and towards my campground at Bigh McGee Lake (bottom right). [Aug.-18, 2025.]

Heading down Hopkins Valley without a trail or difficulties, I reached Mono Creek at 9,300′ (2800 m) in the afternoon. I navigated an unexpected cliff above the treeline (easily done) and a massive pile of fallen trees (harder) that forced me to bush-wack for an hour. Escaping the mosquito infested Mono Valley, I camped a mile uphill at the georgeous Fourth Access Lake. It featured an outstanding and flat campground in the pines with views of lake, mountains, and waterfall; someone even had made a most comfortable bench out of wood. The lake was nearby and I had both an evening and morning swim before heading into Pioneer Basin. The Lake was also stoke full with trout:

Campground at Fourth Recess Lake (top left), my swimming spot among the wooden logs and trout (bottom left), and the view from my camp (right panel). Two people camped on the other side of the lake. [Aug.-19, 2025.]

A short 3 hour walk the next morning got me to Pioneer Basin where I dropped my backpack at 11 am to spent the next 2 hours looking for a place to pitch my tent for the next 3 nights. It was surprisingly hard to find the right spot, but I found it after talking to a young man in his mid 30ies who had just “skied” down Hopkins Peak. Inspired by him, I did something similar the next day, but first he helped me find a good camping sites. I generally like to sleep under trees, pine trees in particular, and I was looking for a shady spot as it was warm and I intended to do some dozing after swimming in the nearby lake. Again, I had many trouts for watching and company, but back to the skiing I did the next day down the upper reaches at Pioneer Basin:

My camp in Pioneer Basin (top left) at the far end of the larger lake with the Fourth Acess Ridge in the background (center left). Fourth Access Valley becomes clearer at bottom left with the many lakes of Pioneer Basin in the foreground as seen from above Standford Col looking south. Looking north from the same location, I see Red Slate Mountain dominating the landscape (right panel). I had climbed it 3 days prior. [Aug.-20/21, 2025.]

Most of the mountains surrounding Pioneer Basin are steep, very steep, but they tend to be a bit sandy, not quite, but the soil on the steep slope is free of bolders with alot of scree, smallish pebbles, really. It is almost impossible to gain traction hiking up such slopes, as one slides down and sinks in. In contrast, heading down such slopes, I found to be like skiing with the hiking poles to keep balance in a controlled slide. Just like skiing one sinks into the scree, slides down, and makes turns by setting poles and shifting balance. What takes 3-5 hours to climb up takes 15 minutes to slide down. Fun … the downhill part that is. So I hiked the basin, swam in 3 of the 7 lakes several times, and even had a lazy day doing nothing but watching the trout in the water, the birds in the sky, and the sun rise and fall. Heaven on earth that I shared with a total of 3 people in 3 days, that is, each person has 2 lakes for themselves every day. And the beaches of the lakes, too, were wild, sandy, and sunny:

Swimming the many lakes of the High Sierra Nevada, I felt fresh and clean and happy. Last year my wife Dragonfly told me to do this also and carry swim trunks, but for some reason I only swam once during the 36 days that I was hiking across mountains and past lakes in 2024. What made this year different was Pavla who picked me up at Tuoloume Meadows. She added to Dragonfly’s suggestions by forcefully setting an example for me. It thus seems that it takes a village to teach an old man new tricks. The swimming will stay with me as lake swimming added a new comfort to the adventure that is hiking for many days and weeks.

P.S.: My 14-day hike covered about 120 miles (190 km), so I comfortably saunter about 10 miles/day with about 40-45 lbs on my back. If pressed, such as by thunder and lightning and rain that hit me the last day at 12,000′ high Mono Pass, I got enough reserves to do an additional 5-7 miles at the end of the day to get down Mono Pass (top left) with Abbot and Dale Mountains in the dark clouds above Ruby Lake. No swimming there … this year.