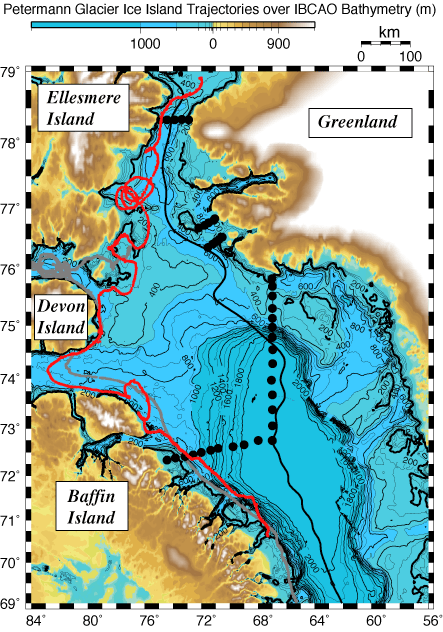

An ice island 4 times the size of Manhattan spawned from a remote floating glacier in north-western Greenland the first week in August of 2010, but it quickly broke into at least 3-4 very large pieces as soon as it flowed freely and encountered smaller, but real and rocky islands. A beacon placed on the ice transmit its location several times every day. It shows a rapid transit from the frigid, ice-infested Arctic waters off Canada’s Ellesmere, Devon, and Baffin Islands to the balmier coasts of Labrador and Newfoundland:

Track of Petermann Ice Island from Aug.-2010 through Aug.-2011 traveling in shallow water from northern Greenland along Baffin Island and Labrador to Newfoundland.

Initial progress was slow as it took the new ice island almost 30 days to wiggle itself free of the narrow constraints of Petermann Fjord:

As soon as it left its home port, it hit broke hit tiny Joe Island on Sept.-9, 2010 and broke into two pieces, PII-A and PII-B for Petermann Ice Island A and B. Not a good start for a new island setting out to sail all the way to Newfoundland where PII-A arrived a year later, but I am getting ahead of my story.

Petermann Ice Island breaks into two segments on Sept.-9, 2010 as seen in this radar image provided by the European Space Agency. Greenland is at the bottom right, Canada top left, the Arctic Ocean is at the top right.

Once in Nares Strait both ice islands experienced a very strong and persistent ocean current. PII-A, about 1.5 the size of Manhattan went first followed by the larger (about 2.5 Manhattans) and thicker PII-B. Their tracks follow each other closely and they almost kiss on Oct.-8, 2010 when both are caught in the same eddy or meander of a prominent coastal current flowing south along Ellesmere and Devon Islands.

Pieces of Petermann Ice Island on Oct.-8, 2010 off southern Ellesmere Island about 600-km to the south of their origin. RadarSat imagery is courtesy of Luc Desjardins of the Canadian Ice Service, Government Canada.

Within a week the larger 136 km^2 piece PII-B breaks into three pieces of 93.5, 28.9, and 11.3 km^2 by Oct.-16 while PII-A stays largely intact at 73.6 km^2. These are all very large islands, the land area of Manhattan is about 60 km^2 for comparison. Some of these pieces approach the coast, some become grounded for a few days to a few weeks, some break off smaller pieces and spawn massive ice bergs that are not always visible from space. PII-A enters Lancaster Sound a week ahead of PII-B on Nov.-14, but exits it within 2 weeks:

Multiple pieces spawned from Petermann Ice Island as seen by RadarSat on Nov.-26 and Nov.-28, 2010 composited and anotated by Luc Desjardins of the Canadian Ice Service, Government Canada.

Notice also the evolution of a string of segments that Luc Desjardins of the Canadian Ice Service identified as pieces from Petermann Glacier. Glacier ice has a darker radar backscatter signature than the sea ice around it. All these pieces eventually enter the Baffin Island Current, a prominent large ocean current that extends from the surface to about 200-300 m depth. The Petermann pieces are moved mostly by ocean currents, not winds, because there is more drag on the submerged pieces of the 40-150 meter thick glacier ice. In contrast, the much thinner sea ice is mostly driven by the winds. This is also the reason one often finds areas in the lee of icebergs and islands free of older ice which is swept away by the winds as the iceberg moves slower as it is driven by deeper ocean currents. I will talk more of these in a later post.

As part of a large oceanography program in northern Baffin Bay and Nares Strait in 2003, we collected ocean temperature, salinity, chemistry, and current data along lines roughly perpendicular to both Baffin Island in the west and Greenland in the east along with the trajectory of PII-A in the fall of 2010 (red dots) and the almost identical track of a much smaller ice island from Petermann Glacier that passed the area in 2008:

Map of the study area with trajectory of a 2010 (red) and 2008 (grey) beacons deployed on Petermann Glacier ice islands over topography along with CTD station locations (circles) and thalweg (black line). Nares Strait is to the north of Smith Sound.

I will talk about these data and the subsequent tracks of PII-A and PII-B from 2010 into 2011 in Part-2 of this summary on how the first of this piece (PII-A) arrived off coastal Newfoundland in the late summer of 2011. Rest assured that there are many more pieces coming to coastal Labrador and Newfoundland in 2012 and 2013 where they put on a majestic display of abundant icebergs such as this last remnant of PII-A as seen from the air on Nov.-2, 2011 in Notre Dame Bay, Newfoundland.