ADDENDUM (Nov.-7, 2012): Time lapse video from Delaware Sea Grant.

Rising seas and flood waters cause most of the damage during storms such as Sandy did last week. Tides, waves, and storms all contribute. We can debate how global warming impacts any of the above, but the arguments are involved. So lets assume, that neither tides, waves, nor storms are impacted by global warming, but that the globally averaged rise in sea level over the last 50 or 100 years is. This global warming induced sea level rise is about half a foot in 50 years (3 mm/year), but why would we care about global averages, when we live in Delaware? Furthermore, why worry about the whimpy surges we get ever 2-3 weeks. We don’t, we worry most about the most extreme events like Sandy and want to know how often they occur. Below I show a Sandy-like event to occur about once every 10 years. Furthermore, over time Delaware’s most extreme storm surges are rising twice as fast as global averages do. So, how much does the global warming impact our local flooding in Delaware?

Market Street on the beach in Lewes is in one of the lowest lying areas of town and takes its good old-time draining. This photograph looks northeastward toward the beach, just west of the intersection with Massachusetts Avenue. [Credit: Cape Gazette]

More than I initially thought: the largest storm surge that has hit Delaware was the Ash Wednesday storm on March 6, 1962 which added 5.8 feet to the regular tides and waves. I wrote about this yesterday using public NOAA data. This same storm today would add 6.8 feet to the regular tides and waves. For comparison, Sandy’s storm surge added 5.3 feet. So Sandy was a weak storm by comparison. If it had hit in 1962, it would have added only 4.3 feet. The difference of 1 foot in 50 years is due to steadily rising sea levels:

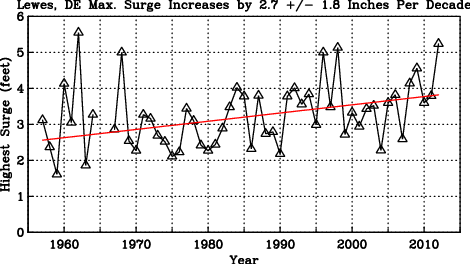

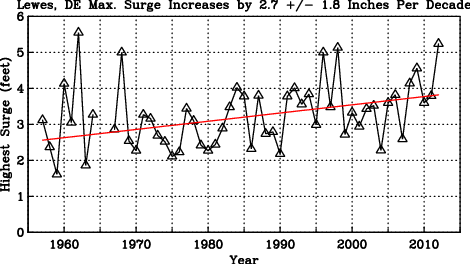

Largest storm surge at Lewes, Delaware each year from 1957 to present. The red line is a linear fit to the data. The slope indicates that the largest storm surge increase by almost 3 inches every 10 years.

On average each year has a larger largest surge than the year before. While this steady increase by 2.8 +/- 1.7 inches each 10 years is statistically significant (95% confidence), picking the extreme each year is perhaps not the best statistic as extremes do not happen often. Please note that a 95% confidence means that there is a 5% chance that the true increase is either smaller than 0.9 inches/decade or larger than 4.5 inches/decade.

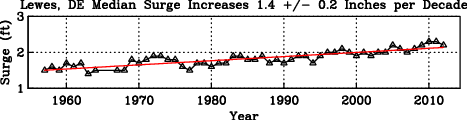

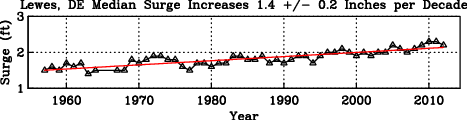

What about the mean or average surge each year? From hourly data, I pick the middle surge, that is, half the surges each year are larger and half are smaller:

This increase of 1.4 +/- 0.2 inches per decade (95% confidence) is more in line of the global average. The uncertainty in this trend is smaller than that of the trend for the extreme, because the median sea level varies little from year to year, while the extreme value varies more from year to year. So, from these results we can conclude, that while the mean or median sea level at Lewes increases by perhaps 1.5 inches in 10 years, the extremes increase twice as fast. So, storm surges like Sandy will become more common than they are today mostly because of global warming.

Over the last 50 years we had at least 5 such events in 1962, 1968, 1996, 1998, and 2012. So, on average we have a Sandy-type storm surge greater than 5 feet every 10 years. This contradicts a Wilmington News Journal article today which quotes John Ramsey to describe “… Sandy as a 1-in-200-years storm, unlikely to be repeated anytime soon. That could give coastal communities time enough to deal with the real threats and realities of sea level rise and climate change.” There is no such time, as it is mis-leading to describe Sandy as a 1-in-200-year event when it has happened about every 10 years during the last 55 years. Instead of a 0.5% percent chance of a Sandy-like event to hit Lewes each year, I would raise this chance to be larger than 10%.