The ice of the Arctic Ocean is rapidly disappearing. This happens every summer, but for the last 30 years there is a little less ice left at the end of each summer than there was the year before. The areas covered by ice are not only shrinking, the ice is also getting thinner, or so many do believe.

To check out such claims, we placed sound systems on the ocean floor of Nares Strait from which to find out how much the thickness of the ice above has changed. We started this in 2003, were told to stop it in 2009, but privately parked our instruments where they would collect data. We must get to check our sound systems and retrieve the private recordings, because otherwise Poseidon will claim our possessions for parking violations. The Canadian Coast Guard Ship Henry Larsen, we hope, will help us to negotiate water and ice to get us deep into Nares Strait as she and her crew did so well in 2006, 2007, and last in 2009.

CCGS Henry Larsen in thick and multi-year ice of Nares Strait in August 2009. View is to the south with Greenland in the background. [Photo Credit: Dr. Helen Johnson]

The ice profiling sonar sounds system before its first deployment in Nares Strait in August 2003 from aboard the USCGC Healy. It measure ice thickness many times each seconds for up to 3 years. View is to the north-west with Ellesmere Island, Canada in the background. Listening in are Jay Simpkins (left), Helen Johnson, and Peter Gamble.

Nares Strait to the west of northern Greenland is one of two major gates for the thickest, the hardest, and the oldest ice to leave the Arctic for the Atlantic Ocean [Fram Strait to the east of Greenland is the other.] This gate is closed at the moment by an arching ice bridge that locks all ice in place. No ice can leave the Arctic via Nares Strait as long as these arches hold. The ice arch acts as a dam that holds back the flood of ice that will come streaming south hard once the dam breaks. And break it will, usually between the end of June and July.

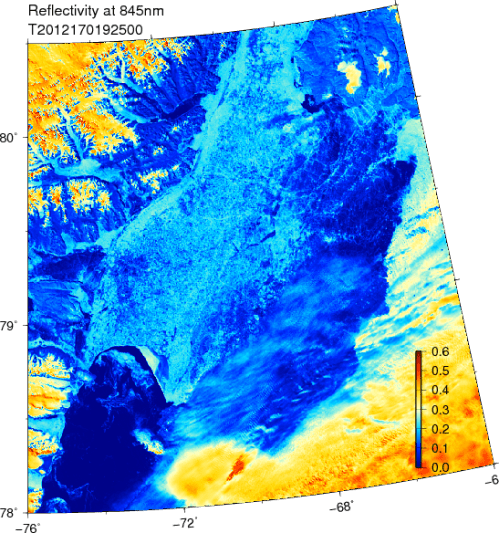

Ice arch in southern Nares Strait as seen by MODIS Terra on June-18, 2012. Greenland is on the right, Canada on the left. The dark blue colors in the bottom-left are open water, yellow are the ice caps of Greenland and Ellesmere Island and lighter shades of blue are warm ice or land. Humboldt Glacier is the on the right-center where Nares Strait is at its widest with Kane Basin at about 80 N latitude.

Nares Strait Jun.-10, 2012 image showing land-fast ice between northern Greenland and Canada as well as the ice arch in the south (bottom left) separating sea ice from open water (North Water). The coastline is indicated as the black line.

The sooner it breaks, the more old ice the Arctic will lose and the better it is for us to get an icebreaker to where must be to recover our instruments and data. The data will tell us if the ice has changed the last 9 years.

I processed and archived maps of Nares Strait satellite images to guide 2003-2012 analyses of how air, water, and ice change from day to day. Ice arches formed as expected during the 2003/04, 2004/05, and 2005/06 winters lasting for about 180-230 days each year. In 2006/07 no ice arch formed, ice streamed freely southward all year, and this certainly contributed to the 2007 record low ice cover. In 2007/08 the arch was in place for only 65 days. In 2009/10, 2010/11, and now 2011/12 ice cover appear normal as the arches formed in December and lasted until July.

We live in exciting times of dramatic change, some to the better and some to the worse. Some of the change is caused by global warming while most is probably not. We do not know for sure, but most of the evidence points towards us people as a major driver of the change we observe in the Arctic and elsewhere. Nevertheless, climate and its change is one grand puzzle that no single scientist, no single discipline, no single country, and no single continent can solve. There are many pieces that all contribute to how and why the Arctic ice changes the way it does. And this includes the ice arches of Nares Strait. There are many mysteries and unresolved physics in what makes these ice arches tick and what makes them blow to bits, but blow they will … watch it, it’s fun, and perfectly natural.

EDIT: This movie shows just how stable the ice arch is at the moment.