Tags

Arctic Ocean climate climate change glaciers Greenland ice ice island moorings Nares Strait NASA oceanography Petermann physics travel weather-

Recent Posts

- Navigating Health and Community in Germany as a Returned Immigrant: Trains, Sport, and Food

- Back-Packing to Pioneer Basin in California’s High Sierra: Beaches and Swimming and Trout

- Exploring Greenland’s Coastal Currents: A Journey of Discovery with Icebreaker Polarstern

- Faith, Freedom, and War: German Summer School in Ukraine

- Walking Lviv, Ukraine: Art, Life, War, and History

Top Posts & Pages

Archive

Topics

-

Category Archives: Nares Strait 2012

Nares Strait 2012: First Mooring Recovered

We have received word back from the intrepid Arctic explorers of some early success. Here is Andreas Muenchow’s latest report:

“Recovered first mooring at 80.7 N and 67.7 W. Ice profiling sonar was hit by ice 100-m below surface, light damage on guard rail, but transducers look ok. Clear skies, light winds from the south, and air temperatures of 1.9 Celsius provided optimal condition. Never before did we recover a mooring this quickly: acoustic interrogation was less than 5 minutes, another 2 minutes after release command the mooring popped up in open water 300 feet from the ship, zodiak lassoed mooring, and 20 minutes later all was aboard. It does not get better than this … attention to detail by Dr. Melling’s mooring group (Joe, Ron, Dave, and Dave) in 2009 paid off.

Petermann Ice Island edged another 1 km towards Nares Strait. I saw at least 3 much smaller segments of likely Petermann Glacier pieces yesterday, all tiny, about the size of our ship. We are now also within helicopter range of Petermann Fjord, but we have 6 more moorings to go. Good start.”

by Andreas Muenchow, Aug.-6, 2012, 12:41UTC

Posted in Nares Strait 2012, Petermann Glacier, Polar Exploration

Tagged moorings, Nares Strait, Petermann

Nares Strait 2012: Approaching Ocean Mooring Line in Kennedy Channel

by Andreas Muenchow, Aug.-5, 2012, 14:22 UTC

From the southern entrance of Kennedy Channel at 80.03N and 67.25W we can see our mooring site about 45 nautical miles ahead, about 80 km. It will take us 8-9 hours to get there as the ship weaves its way through ice that covers about 50-80% of the surface. The farther north we get, the thicker and harder the ice. Air and ocean temperatures are lower, less ice melt has taken place, and we are closer to the source of this multi-year ice. The very clear skies, clean air, flat ocean, and rugged ice provide ideal conditions to fool the eyes and brain of even experienced sailors: mirages are everywhere as the light is reflected and refracted so many times that not all we see is what it is. Even renowned polar explorer Robert Peary saw land in the 1890ies where there was none, called it “Crocker Land” to honor one of his sponsors, and subsequent explorer toiled in vain to find it.

We are ready and eager to start work in earnest after 2 days of sailing. The recovery of the instruments anchored to the bottom of the ocean for the last 3 years has the highest priority. We need the instruments aboard to get to the data that describe ocean currents, temperature, salinity, and ice thickness at least every half hour continuously since August of 2009. Should the ice prevent us to reach every site, we are prepared to service the automated weather stations, like the one at Hans Island. Dr. Jeremy Wilkinson is hosting the data here in real time. Hans Island is a short distance north of our mooring line. Tonight we will start to measure ocean temperatures, salinity, and densities with depth at 5-7 stations running along a section from Ellesmere Island in the west towards Greenland in the east. The term “night” has no meaning, however, as the sun is always brighter than it is in my garden in Delaware because there is no shade and ice and water reflect all light along multiple pathways.

At 6 am this morning I saw a ship-sized piece of ice from Petermann Glacier in the distance. It had the undulating surface that is typical of Petermann as well as dirt from rock. Nevertheless, do not know where the Manhattan-sized Petermann Ice Island PII-2012 is right now or if it has left the fjord. Internet access is severely limited for scientists and crew alike. So you, my dear readers, probably know more than anyone aboard this ship where PII-2012 is from browsing NASA’s MODIS archives, if the area is cloud-free.

The helicopter left the ship half an hour ago with the ice observer and two scientists aboard (Allison Einolf and Dr. Renske Gelderloos) to reconnoiter local ice conditions up to Hans Island 60 miles ahead. While a prudent mariner in these icy waters will always inspect ice conditions ahead via helicopter to extend the 3-12 mile radar range, the helicopter is also an expensive resource at $1,800 per hour. For example, with the currently clear skies overhead NASA’s MODIS provides 250-m resolution bands that are good for ice navigation in Nares Strait, if they were available. RadarSat is even better, but even RadarSat is received aboard the ship only at downgraded resolution to reduce data transmission rates and costs.

Addendum: The helicopter returned safely with images and videos of ice conditions in Kennedy Channel. Also, as of 2 minutes ago: “In theory we do know where PII-2012 is as this morning’s RadarSat image include Petermann Fjord,” said Ice Service’s Specialist Erin Clark before heading off for lunch after getting off the helicopter.

Posted in Nares Strait 2012, Polar Exploration

Tagged ice surveillance, Nares Strait

Nares Strait 2012: Grounded in St. John’s, Cod, and Crossing of Lines

Hurry-up and wait: The rushed 5 am arrival at St. John’s airport this morning turned into a six-hour wait and a canceled departure for Thule, Greenland. Crew, officers, and scientists are all grounded and spend an extra night waiting. There is lots of talk about screeching-in and uncertainty if membership in the “Order of the Blue Noses” or the “Order of the Gold Dragons” substitutes the more mundane “screeching-in.” Let me explain:

The CCGS Henry Larsen originates from St. John’s and most of its officers and crew are local to the town, island, and icy waters offshore where cod once ruled supreme until mis-managed industrial-scale offshore trawling almost wiped the cod out and destroyed much of the local economy that was based on cod for centuries.

Time series of (a) catch of cod (in 106 tonnes) over the Newfoundland and Labrador shelf (b) the total abundance of Gadidae over the southern Newfoundland shelf (c) the catch of shrimp and (d) crab over the Newfoundland and Labrador shelf (e) the greenness index from the Continuous Plankton Recorder (CPR) over the southern Newfoundland Shelf (f) bottom temperature from inshore on the southern Newfoundland shelf and (g) the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) index. The heavy solid lines in panels (f) and (g) represent low-pass filtered smoothed curves of the plotted data. [From DeYoung et al, 2004: Detecting regime shifts in the ocean, Prog. Oceanogr., 60, 143-164.]

The CCGS Henry Larsen has two crew who rotate on and off the ship every 4-8 weeks. Over the years I have met many crew who hailed from families who had worked the cod on smaller, inshore boats. They are superb and experienced sailors who know how to handle and run ships and all attached to it in harsh and icy waters. But how does this relate to screech and cod? Let me digress a moment by comparing US and Canadian Coast Guards:

The U.S. Coast Guard’s ice breaker operates 24-hours/day under military rules without alcohol or overtime to be had. In contrast, the civilian Canadian Coast Guard operates less hours at full strength with some alcohol and some overtime served in moderation. The cultures aboard US and Canadian vessels differ: US ships are permanently in training with young crew on 6-month deployments moving to a new assignment each year, while Canadian ships are working with an older, more experienced, and steady crews. The Canadian crews do the same amount of work in 12-18 instead 24 hours with 1/3 the staff. Ironically, US ships have more “unclassified” electronic capabilities with many more advanced sensor systems. Both ships also have “classified” sensors and missions that I know nothing about, but I digress. Cod and screech are potentially aboard Canadian ships operating out of Newfoundland only.

CCGS Henry Larsen crew at work: Deployment of a tide gauge (subsurface pressure sensor) in Alexandra Fjord. This is one of the instruments we will recover from Nares Strait that was deployed in 2009.

Our small motley crew of eight scientists this year consists of 4 Canadians from British Columbia, 3 Americans from Delaware, and 1 Dutch from England. Yesterday night we all converged at a fine restaurant on Ducksworth Street in downtown St. John’s, Newfoundland. A dispute is still raging among us on what is valid proof of earlier”screeching-in?” I learnt the hard way, that “laminated certificates” are invalid, but what about “un-laminated certificates?” The former are easily obtained in the vibrant port city of St. John’s with its many bars and pubs. The “un-laminated certificates” may be valid, if signed and authenticated by an officer of the CCGS Henry Larsen aboard said ship, but enforcement has been selective.

There are also arguments, that a crossing of the Arctic Circle (certified by a Commanding Officer of a Canadian Coast Guard ship) or the crossing of the International Dateline north of the Arctic Circle (certified by a Commanding Officer the CCGS Henry Larsen) may supersede the more common “screeching-in” ceremonies and certificates. I am the main person making these arguments facing authorities with powers that exceed mine by far.

Our failure to leave for Thule, Greenland today may give some of us a chance to get potentially needed “screeching-in” certificates, but I very much doubt that these “laminated certificates” carry much weight. Time will tell. It will also tell if we get to Thule tomorrow. Hurry-up and wait.

Nares Strait 2012: First Challenges and Petermann Ice Island Coming

Petermann Glacier’s 2012 ice island is heading south, the Canadian Coast Guard Ship Henry Larsen is heading north, and my passport went through the washer. Ticket agents at Philadelphia airport refused to accept my worn passport to get into Canada. My journey appeared at a dead-end, but ticket agents, U.S. State Department employees in downtown Philadelphia, and a Jordanian cab driver got me to Canada with a new passport, a new ticket, and a new lesson learnt in 4 hours. I did not believe it possible, but it was. I arrived in Canada with an entire day to spare.

Over the years I learnt to plan and budget generously for Arctic research, and then improvise with what is available. I was taught to bring spares of all critical equipment to prepare for loss and failure. I learnt to allow for extra time as missed planes, weather, and who knows what always make tight schedules tighter, like passports going through washers. I learnt that patience, civility, co-operations, and seeing the world through other people’s eyes and responsibilities get me farther than fighting. After I got my PhD in 1992, I learnt that the very people who cause troubles by enforcing rules and regulations are often also the most likely to know the way out of trouble. The ticket agent who denied my passport was also critical to help me get a new one. Thank you, Beth.

Our science party of eight from Delaware and British Columbia and the ship’s crew of 30-40 from Newfoundland will meet on the tarmac of St. John’s tomorrow at 4:30am, fly to and refuel at Iqaluit, Nunavut, and arrive at the U.S. Air Force Base at Thule, Greenland. The crew who got the ship from St. John’s to Thule will return with the plane home. It usually takes two days sailing north by north-west to reach Nares Strait from Thule, but this year the ice will be a challenge far greater than getting a new passport in 4 hours.

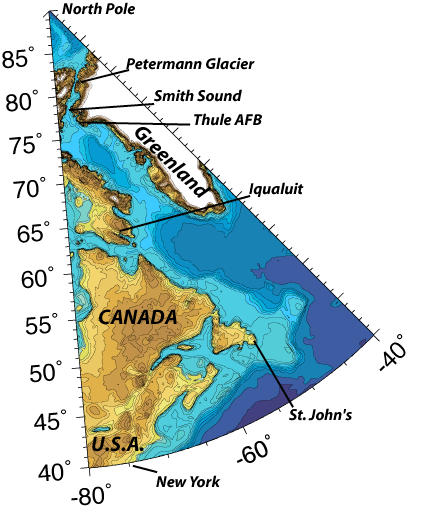

Western North-Atlantic and Arctic regions with Greenland in the west (top right) and Canada (left). Blue colors show bottom depth (light blue are shelf areas less than 200-m deep) and grey and white colors show elevations. Nares Strait is the 30-40 km wide channel to the north of Smith Sound, Baffin Bay is the body of water to the south of Thule.

The ice island PII-2012 is moving rapidly towards the outer fjord at a rate that increased from 1 km/day last week to 2 km/day over the weekend. I expect it to be out of the fjord an in Nares Strait by the weekend when we were hoping to recover the moorings with data on ocean currents, ice thickness, and ocean temperature and salinities that we deployed in 2009. The ice island is threatening us from the north: Without a break-up, it is big enough to block the channel as another large ice island did for almost 6 months in 1962.

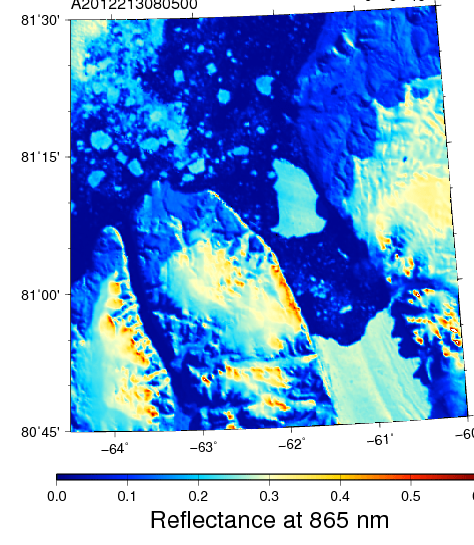

Petermann Glacier, Fjord, and Ice Island on July 31, 2012 at 08:05 UTC. Nares Strait is to the top left. Petermann Glacier, Greenland is on bottom right. PII-2012 is at the center.

At the southern entrance to Nares Strait, lots of multi-year ice is piling up near the constriction of Smith Sound. Winds and currents from the north usually flush this ice into Baffin Bay to the south, however, the same winds and currents will move the ice island out of Petermann Fjord and into Nares Strait. We will need patience, humility, and luck to get where we need to be to recover our instruments and data. A challenge that cannot be forced, we will likely wait and go with the flow rather than fight nature. We will have to play it smart. We are the only search and rescue ship for others. I am nervous, because this year looks far more difficult than did 2003, 2006, 2007, or 2009. In 2005 we were defeated by the winds, but that is a story for a different day.

Posted in Ice Island, Nares Strait 2012, Petermann Glacier

Tagged atlantic, continental shelves, Greenland, Labrador, Nares Strait, Newfoundland, Petermann