Allison Einolf, Aug.-7, 2012

I know next to nothing about helicopters. They’ve always seemed exciting, but I couldn’t tell you anything about make or model or what makes one helicopter better than the next. As it turns out, helicopters are just as exciting as they seem on television.

Sunday morning, as our group of eight scientists met to discuss the plan for the day, Brian, the Chief Officer, interrupted to ask if anyone wanted to tag along on the first helicopter ride of the trip. Renske’s hand immediately shot up into the air, and I volunteered a little more slowly. We quickly wrapped up our meeting, and Renske and I layered on jackets and headed up to the flight deck.

Allison Einolf getting ready for an ice recon flight on the flight deck of the CCGS Henry Larsen. [Photo Credit: Jo Poole, British COlumbia]

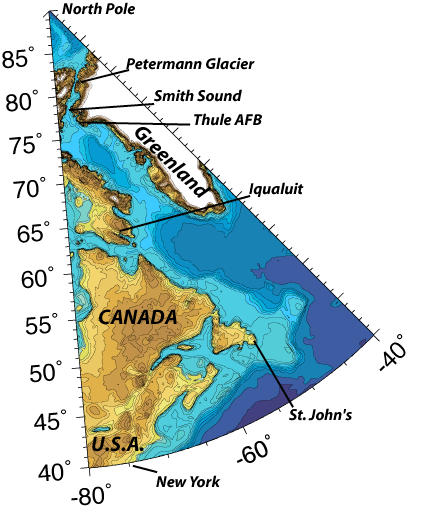

The purpose of the flight was to give the Ice Services Specialist, Erin, a chance to look ahead at the ice cover up to Hans Island, where we were headed. She was going to make a chart of the ice to help guide the ship through the path of least resistance, and maybe do a little sightseeing. An air of excitement filled the helicopter because neither she nor the pilot, Don, had ever been up here in Nares Strait either.

Once the first bit of work was done, we flew over to Ellesmere Island to see the amazing folded ranges. The colors there are amazing – bright reds and yellows in layers, crunched up in beautiful synclines and anticlines. The hills are scored with avalanche chutes and based with alluvial fans. There are glaciers nested in the folds of the mountains, and it is simply breathtaking.

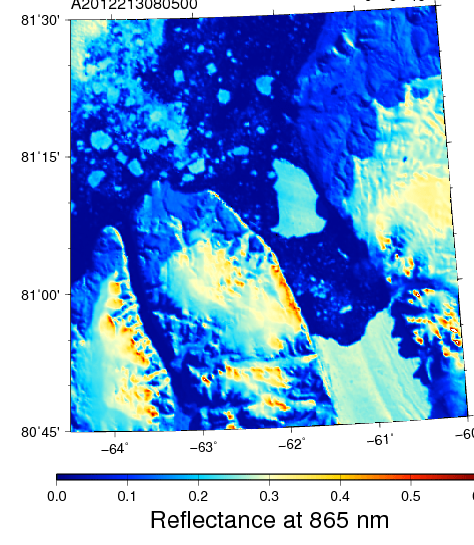

There is a stark contrast between Greenland and Ellesmere Island on either side of the Kennedy Channel. I was awestruck by Greenland while we were in Thule, but Ellesmere Island makes the Greenland side of the strait look dull and gray in comparison. It’s one of the first things you notice up here, and many members of the crew point it out on sunny days. The contrast brings up all sorts of questions about the rocks even for the casual observer.

A few theories have come up over the years as to what made the sides of the channel so different. Some think that the channel lies along some sort of fault or plate boundary, and some argue that plate tectonics has nothing to do with it. No matter how I look at it, something has to have been vastly different on each side of the strait because the Greenland side has all of these horizontal layers in a much grayer rock, and the Ellesmere side is more than just colorful layers – they bend and contort in violent and beautiful ways that seem much more active than the Greenland layers.

Both sides of the Nares Strait are beautiful in their own ways, and the view from a helicopter was spectacular. We were able to land on Hans Island, which is a great example of the carbonate rock of Greenland, and is apparently rife with marine fossils. We also flew over Franklin Island and farther south to Rawlings Bay and Jolliffe Glacier. It was the first time I had seen a large glacier close up, and it was amazing to see the ridges in the ice, and I was surprised by how much a glacier seems to look and act like a very slow moving river.

CCGS Henry Larsen as seen from atop Hans Island. The view is to the west with Ellesmere Island in the background. [Photo Credit: Allison Einolf, University of Delaware undergraduate intern]

As we flew into the fjord, I was continually amazed by how nearly vertical some of the layers of the rock were, and by the bright reds and yellows of the rock. Flying back to the ship we flew over the mountains and I was amazed by the way the rock beneath us dropped away completely as we flew into Nares Strait. The geology, the ice, and the experience of being in a helicopter were all so incredible.