Sleeping and camping in California’s Wilderness requires a permit. The most desired permit starts in Yosemite National Park to hike the 220 mile John Muir Trail (JMT) through Yosemite, Kings Canyon and Sequoia National Parks as well as Ansel Adams, John Muir, and Golden Trout Wilderness. This spectacular and scenic hike along the spine of the Sierra Nevada takes 3-4 weeks to complete without ever crossing a road or seeing a car. Chances to score a permit are slim (less than 1:10), so about 9 out of 10 applicants fail to win this “Golden Ticket” via a lottery. Last year I was one of the 9 and thus had to be creative, because I wanted to hike the JMT. Here is my “solution” from 2024:

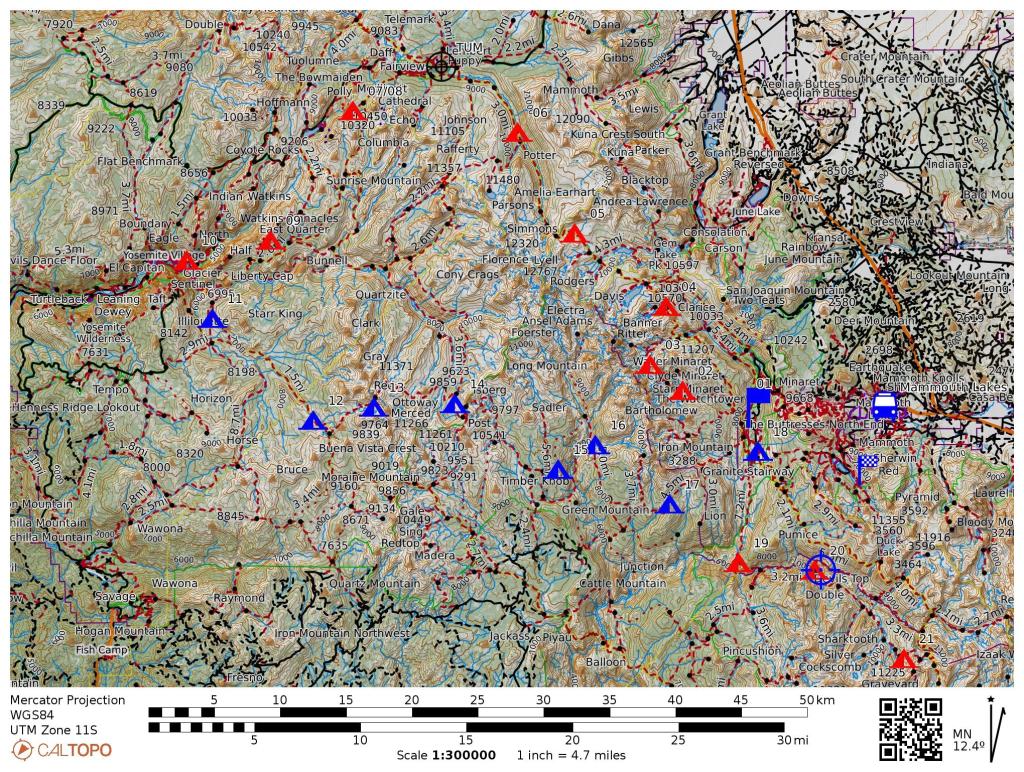

My 2024 loop through Yosemite National Park. I acclimated at Mammouth Lakes (blue bus) for 2 days and took a city bus to my trailhead at Devils Postpile (blue flag). From there I hiked north to Yosemite Village via Donahue Pass along 8 campsites (red tents). This was my first permit. The second permit carried me from Yosemite Village via Red Peak Pass and Isberg Pass along another 8 campsites (blue tents) back to Mammouth Lakes. Subsequently, I continued walking on the same second permit south loosely following the John Muir Trail (JMT) and past it to Horseshoe Meadow near Lone Pine, CA.My solution included two different, easy-to-get permits to loop counter-clockwise through Yosemite. Starting at Mammouth Lakes (Devils Postpile trailhead), I first headed north loosely following the JMT by crossing Donahue Pass (11,067′ or 3370m high) to reach Tuolumne Meadows (8,619′ or 2630 m low), Clouds Rest, and finally Yosemite Village. Resupplying there, I picked up my second permit, and hiked south back to Mammouth Lakes via Red Peak Pass in the Clarke Range. Back on the JMT at Devils Postpile 8 days later I slept at Reds Meadow (camp #18) to walk south for the next 18 days to complete my own JMT Plus.

The return loop through Yosemite added 82 miles, but these 82 miles required a different set of physical and mental skills, because away from the JMT both people and trails disappear intermittently for days which does not happen on the JMT. The gallery below shows my camp #9 above Half Dome (top left), myself on Clouds Rest (top center), and Cathedral Mountain seen from Lower Cathedral Lake (top right) either on or near the JMT. The larger bottom photo shows the Clarke Range in the distance that I crossed 5 days later. I took the photo above Clouds Rest before descending to Yosemite Village the next day.

The JMT is a shoulder-wide super-highway through the wilderness. The trails are always well maintained and one meets about 10 to 30 people every day from all over the world of all ages. Only on the last 5 miles past iconic Half Dome into Yosemite Village 100s or 1000s of people moved up and down the trails for the day. Sleeping at the backpacker’s campground in Yosemite Village (camp #10) for $8, I splurged on an awesome $40 breakfast at the majestic Ahwahnee Hotel. These are my priorities and I was back on serene trails turning right (west) near Nevada Falls to head up towards the Illilouette Valley. The last day hikers were a lovely couple from Lithuania with their two lively and happy children. Two hours later I reached the Illilouette watershed where I slept solidly on a thick and soft bed of pine needles (camp #11).

The next two days I only met one group of 2 hikers on my way to Merced Pass Lakes (camp #12) and nobody to Ottoway Lakes just below Red Peak Pass in the Clarke Range. My campsite #13 in the top-left photo below is the small flat area in the shade next to a 20 feet high block of granite. My view towards the west included Merced Peak at 11,726 feet (3574 m) and nearby patches of snow.

The photo above shows Merced Peak the tallest mountain of Yosemite’s Clarke Range. I crossed this range the next morning via 11,150′ (3400 m) high Red Peak Pass from where the photo above was taken at 8 am in the morning. The many switchbacks made this an easy hike both up and down into Merced Valley. Here I met, surprisingly, a group of 2 women from my home state of Delaware: we are a small and flat (<480′ or 140 m) state. Crossing the Merced River at 9,150′ (2790 m) elevation, I climbed up again towards Isberg Pass at 10,510′ (3200 m). The Delaware women told me that a snow storm was predicted the next day and stormy it was, indeed, at my campsite #14. Clouds and wind bursts rolled in and out over Isberg Pass all night and the next day. Without breakfast I left this unpleasantly cold and windy camp at 6:30 am to stay ahead of the snow storm trying to reach lower elevations. Easier said than done …

My old Tom Harrison paper map of Ansel Adams Wilderness showed a “maintained trail” for the next 16.6 miles to Hemlock Crossing (7555′ or 2300 m), a bridge across the North Fork of the San Joaquin River, and another 16.9 miles to Devils Postpile via Granite Stairway (9014′ or 2750 m). Such mileage usually takes me 2-3 days of comfortable walking, but this specific hike took me 4 long and exhausting days of navigation through dense brush and forest often without a trail. I gained a new respect for those who initially explored this wilderness 150 years ago without the contour maps, satellite navigation, text messaging, and SOS buttons that I had with me.

Almost immediately after crossing Isberg Pass, the trail disappeared. No problem here, because at ~11,000′ one is well above the tree line and thus sees clearly where one has to go. It is not hard to boulder over large rocks or walk on flat benches of granite or stroll down gently sloping dry stream beds. Furthermore, as soon as the trees reappeared near 9,500′ the trail reappears also. About half way between Isberg Pass and its trailhead near Clover Meadow Ranger Station I met the last group of people for the next 3 days. They were led by a “preacher” my age (63 years) without a backpack and four disciples ~20 years younger who carried heavy loads for their 4-5 day “revival” at Turner Lake in Yosemite. They were friendly, tried to convert me with good humor, and we talked for about 20-30 minutes about nature, god, and life as we know it, but then they headed up towards Isberg Pass and Yosemite while I headed down towards Bugg Meadow and Devils Postpile. All good.

Three hours later the trail almost disappears as I turn east at Detachment Meadow away from all trailheads. The trail becomes fainter with every mile, yet suddenly a posted junction sign points me towards Bugg Meadow and Hemlock Crossing. Good, this is my destination, but the trail immediately disappears. I pitched my tent (camp #15) near a fire-scarred rocky out-crop 2000 feet above the mighty valley the North Fork of the San Joaquin River just before it started to sleet. The next 3 days were the most difficult of my 35 days in the mountains:

All the above photos are on and along this disappeared “maintained” trail where most trees had burnt in many prior forest fires, the steel bridge over the San Joaquin River at Hemlock Crossing had washed out 2022, and snow, rain, and sleet drenched me. Not the best conditions to navigate by map, compass, and GPS altitude through chest-high, wet brush. Wilderness.

Wet, hungry, and discouraged I reached Hemlock Crossing at noon on Aug.-24, 2024 and discovered its badly damaged bridge. What to do? Rest, eat, and dry out before deciding. Feeling refreshed after a large, warm, hour-long lunch and dry clothes, I decided that the twisted bridge was unsafe to use, but that several logs downstream perhaps offered a better way across the swollen river. Strapping my backpack very tightly to my shoulders, I slid on all fours onto and along two large logs hugging them tightly. A climb over a smaller log lodged across the two larger logs was an added challenge (see photo below top left). This “bridge” was above a 20 feet waterfall downstream and a deep pool of water on the upstream side. I cried on the other side happy to be alive.

Furthermore, there was a trail on the eastern side of the San Joaquin heading both north towards Bench Canyon and Lake Catherine below Ritter and Banner Mountains and heading south towards Mammouth Lakes where I headed, but again I was soon on my own again without a trail. The path looks pretty clear on the map along a steeply sloping V-shaped valley near the 7,460′ contour, but where my boots hit the ground along this contour were just walls of brush, meadows, overgrown puddles of water, rocks, fallen logs. At one point I dropped my back-pack to move up the slope to 7,700′ to reconnoiter to find a path forward. There was none for 4 hours until I reached Iron Creek where I stayed for the night (Camp #16).

The sun emerged again the next day (Aug.-25), but the trail disappeared again within an hour from camp, but now I was in a dry forest that had not been burnt too badly and the map told me to go uphill. I did so for most of the day getting away from the treacherous San Joaquin River. Trouble awaited only in the meadows as here the terrain was wet, level, and overgrown with brush. My spirits lifted, however, when I noticed wild Elderberries. The photo above (bottom left) shows their blossoms, but later I found big, dark, black elderberries that I devoured after cooking them. The names of the meadows in the forest without a trail invoked emotions, too, such as “Naked Lady Meadow” followed by “Earthquake Meadow” followed by “Headquarters Meadow” followed by “Corral Meadow” followed by “Cargyle Meadow” before I reached a meadow without a name at the end of the day. These names tell me that people traveled and lived here in the past. There probably are stories that I do not yet know.

My senses sharpened during this day without a trail as I noticed more and more fallen tree logs that had a flat cut surface. At first I recorded each such sighting with its GPS position, but over time I could tell where they were. In the middle of these wild wanderings along a disappeared trail, I found this sign post (top left below) pointing out that this is the intersection of the trail to Mammouth Lakes to the right and Iron Mountain straight ahead. My navigation was good, but the so-called trail after this point was just one pile of wood after another pile of wood where I had to climb over, under, or walk around. Looking back, I find it amazing what one gets used to and how much punishment my then 62-year old body was able to take. After 10 miles of this I made camp at the unnamed meadow at 8,577′ (2610 m) below “Stairway Meadow,” “Granite Stairway,” and “Summit Meadow.” After that, a JMT-type trail emerged that led me down the mountain for 8 fast and furious miles downhill to Reds Meadow. Here civilization expressed itself in the form of a shower, beer, and double cheeseburger in that order. These last 8 miles passed faster than the prior 2 miles navigating wood piles:

Did my solution work? Yes it did for me in 2024, but it may not do so for everyone. During the 8-day return loop via the Clarke Range and North Fork of the San Joaquin River I met three other hiking groups: First 2 students from San Francisco, then the 2 women from Delaware, and finally the friendly “preacher” and his disciples. That was it in terms of people for 8 days. Along the way I learnt to read and interpret both the map and the landscape in front of me.

What served me well was to always listen to my body. I was NOT fighting to reach a destination. I walked only as long as it was fun (mostly) and always stopped for an hour or two when I felt like it. I took off my pack to investigate a pretty flower or a bee on it, watched a bird, or picked wild Elderberries, Red Currants, Rasberries, and even Blueberries. I made camp when I felt like, I was prepared to go home any day that was not fun, completion of the JMT or a certain section was not important. Some days I felt like walking 6-7 miles, but on other days it was 12 miles (to reach that cheeseburger at Red Meadow) or 17 miles (my last day on the trail to reach Lone Pine). It also made me enjoy the well maintained John Muir Trail the next 18 days.

Now, would I do this exact hike again? Probably not, but only now do I know how to read a map of what is out there. In the future I will focus on the many trails that intersect with JMT. That’s where you will find me. The JMT is the scenic highway that leads to all the others. Two days after my shower and cheeseburger at Reds Meadow, I found the Hot Springs of Fish Valley (camp #20). [Photo Credit to Justin from Bend, Oregon; he appeared out of nowhere from above, staged, and took the picture. I met him several times again the next 10 days, but that’s another story.]

So, my next solution would be turn east at Toulumne Meadows and then turn south to cross Parker Pass (11,115′ or 3390 m), Koip Peak Pass (12,280′ or 3740 m), and Agnew Pass (9,900′ or 3320 m). Then follow the Pacific Crest Trail along the Middle Fork of the San Joaquin River back to Mammouth Lakes.