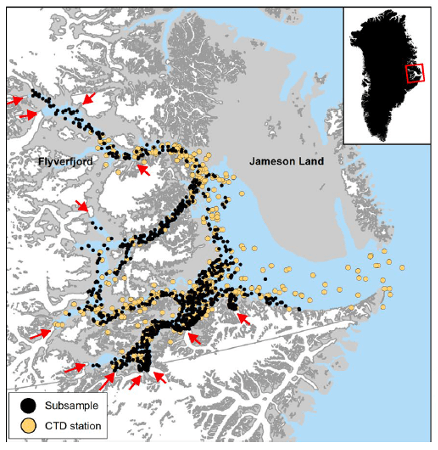

Having spent my whole life in Maryland, I know very little about narwhals or Greenland. When presented a figure of the distribution of 12 tracked narwhals (Figure 1), I noticed that these mammals spent the majority of their time away from the mouth of the fjord (Heide-Jørgensen et al., 2020), and that the fjord looked similar to the geography of the Chesapeake Bay in Maryland. To understand why the narwhals may prefer water near the tributaries to the fjord, I compared it to recorded locations of dolphins in the Chesapeake Bay.

Data collected during a study on temperature-dependent habitat selection for narwhals displays 10 locations per day of 12 narwhals in Scoresby Sound in Greenland for a total of 1,000 positions (Heide-Jørgensen et al., 2020). The narwhals were tracked using satellite-linked time-depth recorders. The mapped positions of the narwhals (black dots) are more concentrated away from the mouth of the fjord complex where Atlantic water enters. Instead, they gather in tributaries on the western side of the fjord where there are active glaciers (red arrows).

The University of Maryland’s Chesapeake Dolphin Watch program (https://www.umces.edu/dolphinwatch) maps citizen dolphin sightings throughout the Chesapeake Bay. Figure 2 below displays the locations of dolphin sightings in 2017 (purple dots), 2018 (blue dots), and 2019 (orange dots). The figure also divides the bay into the upper bay, middle bay, and lower bay, with the lower bay closest to the Atlantic Ocean (Rodriguez et al., 2021). Within these divides, the majority of dolphin sightings are recorded in the upper bay, and overall more dolphins were sighted on the western side of the bay. The dolphin sighting distribution in the Chesapeake Bay in 2017-2019 resembles narwhal distribution in Scoresby Sound, Greenland. Both dolphins and narwhals appear to be found away from the mouth and instead in the tributaries.

Because of my familiarity with the Chesapeake Bay, I know that fresh water enters the bay from the tributaries and meets with salty water that enters from the Atlantic Ocean, which can be confirmed with salinity data available from the Chesapeake Bay Program (Reynolds, 2019). Applying this understanding to the Scoresby Sound, salinity is lowest where fresh glacial melt enters the fjord from the tributaries, as marked by red arrows in Figure 1, and salinity is highest where salty ocean water at enters the fjord at the mouth. Because the distribution of dolphins in the Chesapeake and narwhals in Scoresby Sound appear similar, and the bay and fjord have a similar pattern of salinity, I hypothesize that narwhals and dolphins prefer low salinity water.

However, while the narwhals in Scoresby Sound were tracked using satellite-linked time-depth recorders, the dolphins in the Chesapeake are mapped from civilian sightings. In Maryland, most people that live along the Chesapeake Bay live in cities and suburbs along the western shore of the Bay (U.S. Census Data from 2020, https://www.census.gov/data.html). Of the approximate 986,305 people that live along the western shore, there were 90 dolphin sightings in 2017, or about 0.912 dolphins per 10,000 people. Fewer people live on the eastern shore of the Chesapeake Bay, and of the approximate 244,798 people, 29 dolphin sightings were reported in 2017, or about 1.18 dolphins per 10,000 people. From this data, more dolphin locations were recorded on the western shore of the Chesapeake Bay as a result of more people living there.

Due to sampling bias, this citizen sighting data from the Chesapeake DolphinWatch program cannot be used to support the hypothesis that dolphins and narwhals tend to stay away from incoming salty water from the ocean because they prefer low salinity water. To better test the hypothesis, more accurate data of dolphin positions in the Chesapeake Bay would need to found by using satellite tracking devices similar to the ones used on the narwhals in Scoresby Sound.

Editor’s Note: Ms. Eleanor Smith wrote this essay as an extra-curricular activity developed from a science communication assignment for MAST383 – Introduction to Ocean Sciences. The editor teaches this course at the University of Delaware and was assisted by Ms. Terri Gillespie in a final formal edit.

References

Exchange for Local Observations and Knowledge of the Arctic. (n.d.). About Narwhals. Retrieved from ELOKA: https://eloka-arctic.org/communities/narwhal/about_narwhals.html

Heide-Jørgensen, MP, Blackwell, SB, Williams, TM, et al.: Some like it cold: Temperature-dependent habitat selection by narwhals. Ecol Evol. 2020; 10: 8073– 8090. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.6464, 2020.

Reynolds, D.: Bay health impacted by record flows. Chesapeake Bay Program, https://www.chesapeakebay.net/news/blog/bay-health-impacted-by-record-flows, 2019.

Rodriguez LK, Fandel AD, Colbert BR, Testa JC, Bailey H.: Spatial and temporal variation in the occurrence of bottlenose dolphins in the Chesapeake Bay, USA, using citizen science sighting data. PLoS ONE 16(5): e0251637. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0251637, 2021.