Ms. Amanda Winton wrote this essay as an extra-curricular activity developed from a science communication assignment for MAST383 – Introduction to Ocean Sciences. The editor teaches this course at the University of Delaware and was assisted by Ms. Terri Gillespie in a final formal edit. ~Editor

“… The intense winds blow against my white fur. The chunks of white, frosty glacial ice float below me. I lift my eyes, scanning my surroundings for my next meal. I see a dark gray mass sliding along the ice a few hundred feet away. My mouth waters as my paws ready for the hunt. I have not eaten, nor seen any prey, in 12 days. I begin my slow and steady pursuit. The terrain below me is rough, unlike the abundant flat sea ice that was my ancestors’ hunting grounds.

It is a little bit more difficult to maneuver, taking more time to get to my prey than I would have hoped. Minutes later, I jump into the water, about to swim to the ice my prey is lounging on. Unfortunately, I grossly underestimated how far away it is, and by the time I swim to this meal, it’s gone. Now I am left with no food, and my stomach grumbles for the fifth time today.”

This short, first-person narrative is written from the perspective of a Greenland polar bear in the summertime. In particular, this polar bear is part of a subpopulation that hunts on a glacial mélange within fjords, rather than on larger frozen ice caps. Of course, I do not know what polar bears think in their pursuits, migration, or other actions. I can only use my own experiences and compassion to imagine their point of view and desires. Based on my biocentric view, all animals have their own importance in the world and are worthy of preservation. Since human intervention causes polar bears to struggle in their own environment, people have the responsibility to save them and recover their habitat.

Polar bears are losing their land due to the indirect and direct effects of human interaction with the environment, called climate change. Atmospheric warming leads to scarce and thinner glaciers, as well as less advancement in the growth season. The breakup of ice in the spring due to melting occurs nine days earlier than it did before global warming was identified in 1938 (Maslin, 2016), and the freezing of ice in the fall occurs ten days later (EPA, 2022). Not only is there less ice, but the ice exists for a shorter period of time. This leads to less territory, which can be detrimental to any species.

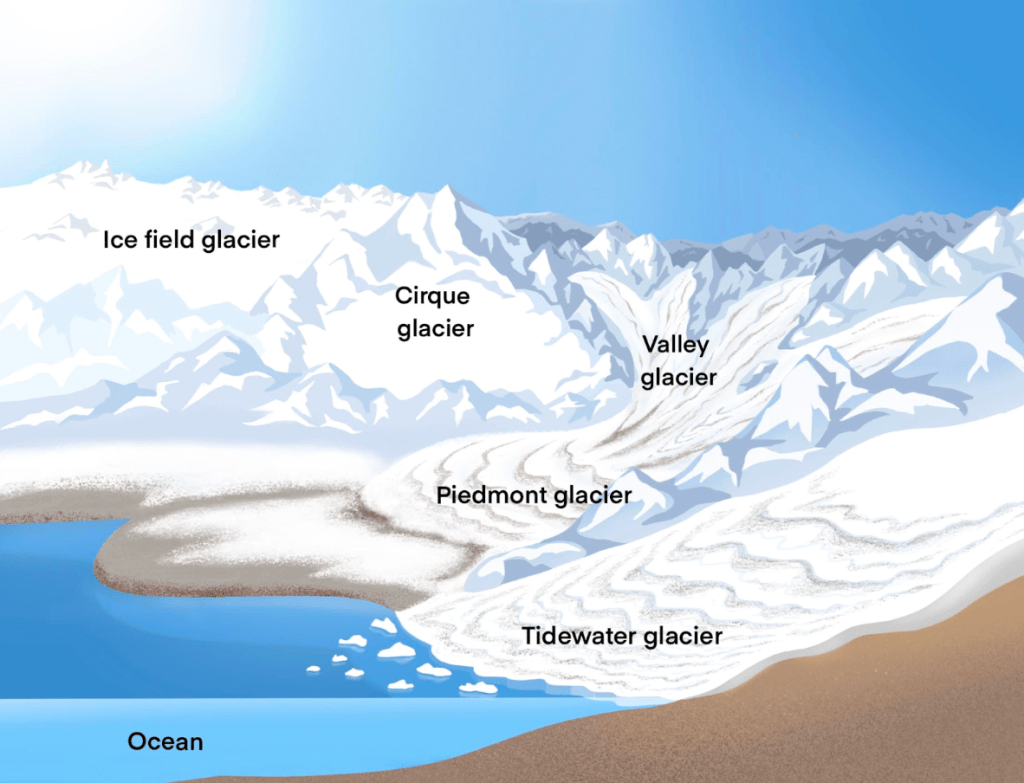

When Glacier National Park in Montana was established in 1910, about 150 glaciers existed. Now, less than 30 remain (Glick, 2021). Polar bears are forced to look for land and food elsewhere because they do not have as much space to hunt and breed. There is not much land or food present, so the natural selection rate for this animal is increasing dramatically every day, at a rate as fast as climate change (Peacock, 2022). Polar bears are forced by their environment to either die or adapt. This is not an easy adaptation, either.

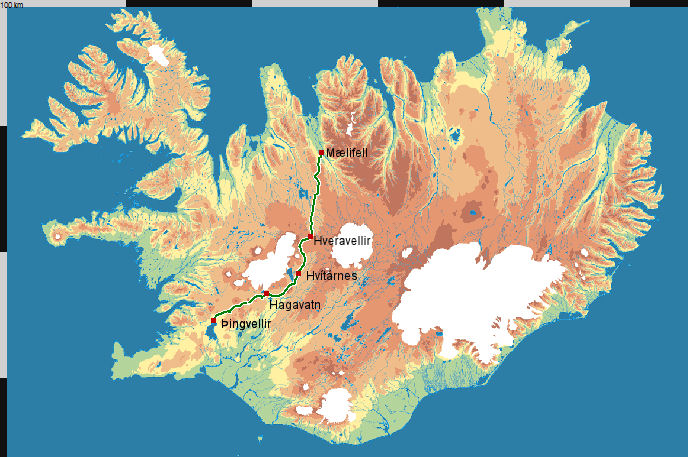

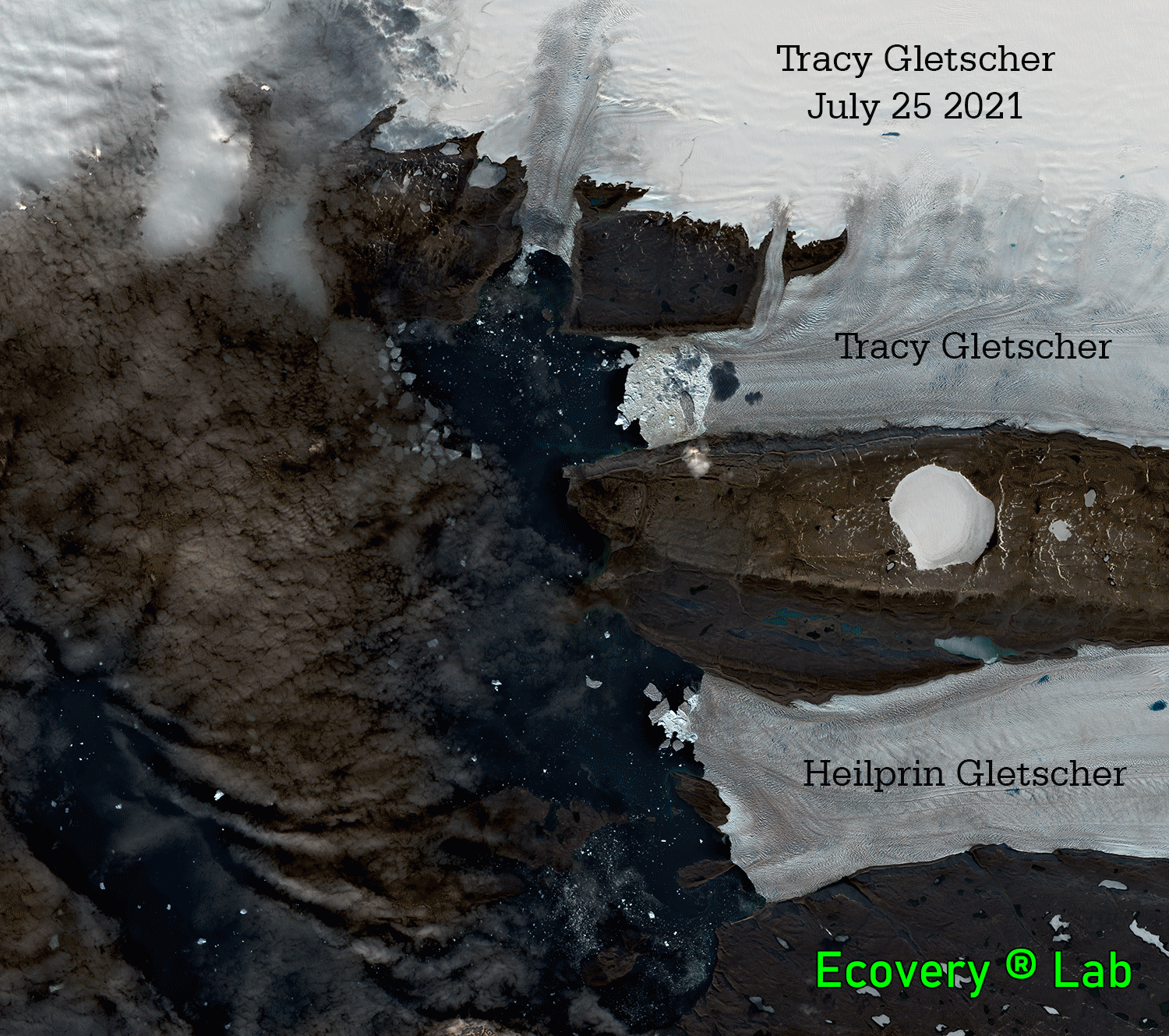

Polar bears are forced to adapt quickly, since glacier ice is very limited in the Arctic. On the southeast coast of Greenland, polar bears have implemented a new habitat: fjords. These bears live at the front of glaciers in fjords, called the glacial mélange, which is a mixture of sea ice, icebergs, and snow. Only polar bears in southeast Greenland live there all year round, using this habitat to breed, hunt, and sleep.

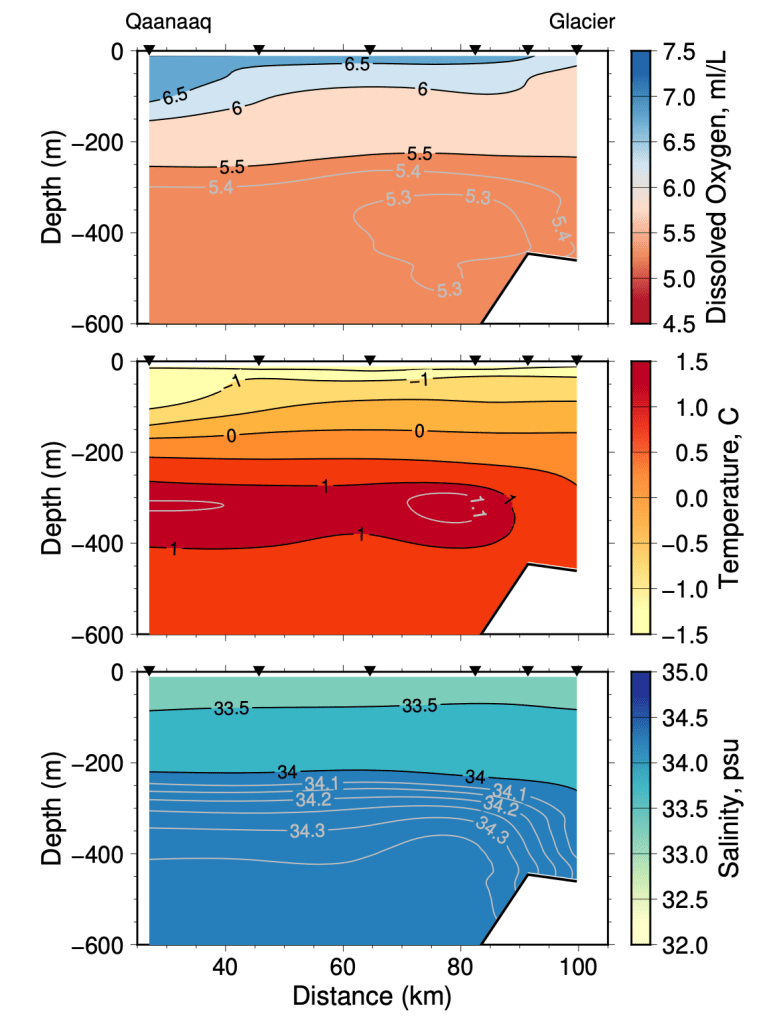

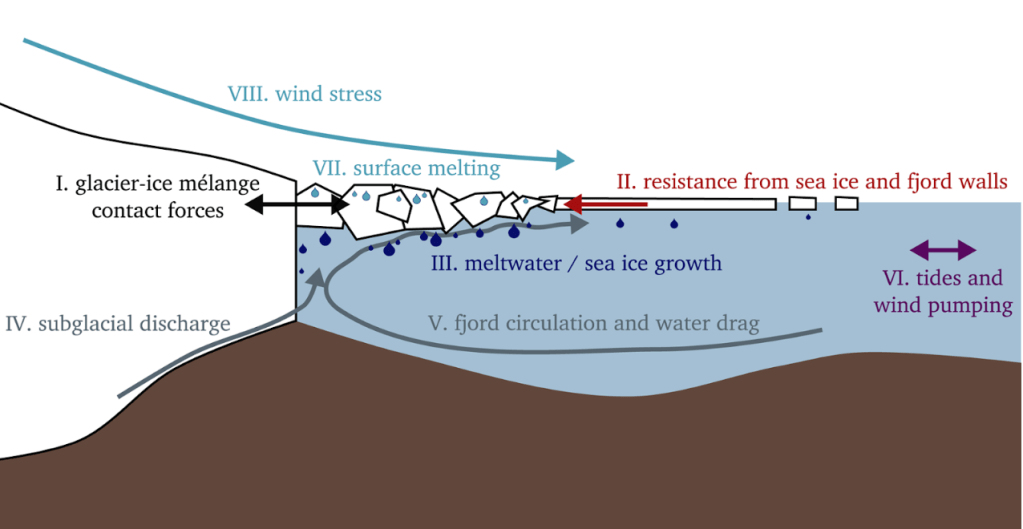

Figure 2. This Glacier-Ocean-Mélange System depicts the forces acting upon this mechanism at all times. These forces are important for keeping the system at equilibrium and habitable for polar bears. [adapted from Amundson et al. (2020)]

In a recent research study led by Kristin Laidre, Northeast and Southeast Greenland polar bear population migrations were tracked. The median distance of the polar bears in the northeast was 40km per four days. The median distance traveled for the southeast population was 10km per four days, which is statistically significantly lower. Laidre et al. (2022) found that the southeast polar bears traveled between neighboring fjords, or stayed in the same fjord all year. This adaptation shows behavioral plasticity (Peacock, 2022), as Southeast Greenland bears have not become locally extinct.

This subpopulation of polar bears is one out of 20, and is very small. They are smaller in size and have a slower reproduction rate, most likely due to trouble finding a mate in a small population, as well as their long generation time and low natality. It’s important to preserve this genetically isolated population to preserve their genetic diversity. Without this element, birth defects, either mental or physical, will occur. This leads to a population less fit for its environment. Genetic diversity is necessary for surviving natural selection and thriving in an ecosystem.

Figure 3. This photograph presents polar bears walking in the snowy fjords. Fjords are not flat, which makes it harder for these bears to travel, versus the flat ice that other polar bears have been hunting on for centuries. [adapted from Laidre et al. 2022]

“… I leave my fjord the next day, hoping to find another nearby, hopefully unoccupied. To my luck, one appears in my field of vision a few hundred meters away. To my surprise, a bob of seals rests on the glacial mélange. They are oblivious and unsuspecting of my presence. Minutes pass, and my stomach no longer rumbles. A successful hunt is always satisfactory. Now I can focus on my next need: my desire to find a mate and pass on my strong genes. It will not be too hard for me as I am a big male, with thick, insulated fur. I advance through the neighboring fjord, hopeful and confident. My story is just beginning.”

References:

Amundson, J., Kienholz, C., Hager, A., Jackson, R., Motyka, R., Nash, J., Sutherland, D., 2020: Formation, flow and break-up of ephemeral ice mélange at LeConte Glacier and Bay, Alaska. Journal of Glaciology, 66(258), 577-590. doi:10.1017/jog.2020.29.

Environmental Protection Agency, 2022: Climate Change Indicators: Arctic Sea Ice, https://www.epa.gov/climate-indicators/climate-change-indicators-arctic-sea-ice.

Dunham, W., 2022: Isolated Greenland Polar Bear Population Adapts to Climate Change. Reuters, Thomson Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/business/environment/isolated-greenland-polar-bear-population-adapts-climate-change-2022-06-16.

Glick, D., 2021: The Big Thaw. National Geographic, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/big-thaw.

Greenfieldboyce, N., 2022: In a Place with Little Sea Ice, Polar Bears Have Found Another Way to Hunt, KTOO, https://www.ktoo.org/2022/06/20/in-a-place-with-little-sea-ice-polar-bears-have-found-another-way-to-hunt/.

Laidre, K. L. and 18 others, 2022: Glacial Ice Supports a Distinct and Undocumented Polar Bear Subpopulation Persisting in Late 21st-Century Sea-Ice Conditions, vol. 376(6599), 1333–1338, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abk2793.

Maslin, M. , 2016: Forty years of linking orbits to ice ages, Nature, 540, 208–209, https://doi.org/10.1038/540208a.

Ogasa, N., 2022: Some Polar Bears in Greenland Survive on Surprisingly Little Sea Ice, Science News, https://www.sciencenews.org/article/polar-bear-greeland-sea-ice-glacial-melange-climate-change.

Peacock, E., 2022: A new polar bear Population, Science, vol. 376(6599), 1267–1268, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abq5267.

National Snow and Ice Data Center, 2022: Glaciers, https://nsidc.org/learn/parts-cryosphere/glaciers/science-glaciers.